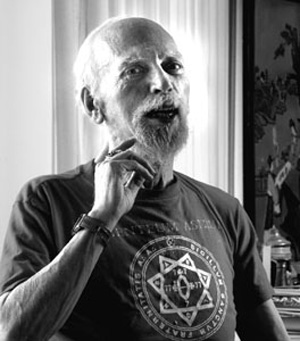

From a certain perspective, Ed Rosenthal may have caught a break when Judge Breyer sentenced him to just one day in prison plus time served when he was convicted for growing hundreds of marijuana plants in Oakland, California. But it would be difficult to argue that his trial was anything short of Kafkaesque. Rosenthal had been deputized by the City of Oakland to grow medical marijuana. But after being busted by the Feds, he was not even allowed to mention his relationship to the lawful government of Oakland nor was he allowed to present witnesses who could talk about it.

So after his conviction, Rosenthal took his case to the United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit and won. His conviction was overturned, but it was overturned on a technicality. Then, in a clear case of vengeful prosecution, the U.S. Attorney for the Northern District of California who prosecuted the case decided to bring up charges again, adding new charges to the original. Again Rosenthal was not allowed to present the obvious defense — his deputization with the City of Oakland — and he was re-convicted.

Before Rosenthal became one of America's best-known martyrs in the "War on Drugs," he was legendary for his work advising pot growers on how to produce the finest gourmet cannabis. His books have included the legendary Marijuana Grower's Handbook and the recent Big Book of Buds, Vol. 3. He wrote the popular "Ask Ed" grower's advice column for High Times during the 1980s and '90s. Rosenthal continues to write "Ask Ed" for the Canadian magazine, Cannabis Culture.

I was joined in conducting this interview for the RU Sirius Show by Steve Robles and Jeff Diehl

To listen the full interview in MP3, click here.

RU SIRIUS: So how long have you been stoned?

ED ROSENTHAL: Well, I only smoke when I'm alone or with people. And I only smoke when I'm awake. I also do food fasts because, you know, life is speeded up. So instead of doing a 24-hour fast, I do, like, 6 hours at a time over a four-day period. It's sort of a fast fast.

RU: Let's talk about your own personal experience with pot. When's the first time that you tried it. How old were you?

ER: Um, I was...

RU: You can't remember!

ER: I was 21.

RU: What year was it?

ER: '65.

RU: It was weak back then, was it not?

ER: Yeah, it was. It was Mexican.

RU: Did you get pretty ripped? Do you remember?

ER: I got stoned enough. I remember thinking, "This is the greatest thing that ever happened in my life." I remember that. I thought that this was going to be a really powerful ally for me. And then, years later, I read the Don Juan books, and there it was.

RU: Did you associate pot in 1965 with beat culture?

ER: Folk music.

RU: And did you think that pot produced insight? Why did you like it?

ER: it was very introspective for me at that time.

RU: So let's talk about the recent wrinkle in you medical marijuana case. Why were you re-convicted, and why didn't you present a defense?

ER: We would've liked to have presented a defense. When you're on trial, you would like to do that. But the judge said he didn't like our defense. For instance, we wanted to talk about the prosecutor's RICO relationship with one of the witnesses. But we weren't allowed to present any of our defenses. One by one, the judge said that we couldn't present witnesses. For instance, we wanted to present Nate Miley, who had been a city councilperson in Oakland. He would've testified that what I was doing was in line with the city of Oakland's regulations, and that I had been deputized as a city officer. I would've brought in Barbara Parker with the city attorney's office, and she would've verified some of those things. And I would've brought end users. You know how prosecutors often bring victims in to court? Well, I would've wanted to bring in the "victims" of my actions. Those "victims" would've been the people who actually received either starter plants themselves, or the marijuana that was grown from the starter plants.

But the judge wouldn't let me do that. He wouldn't let me say to the jury that I was an officer of the city of Oakland. I couldn't testify that I had been deputized to do this and that I had been assured that I was free from prosecution.

RU: You mentioned something about the prosecutor having a RICO relationship with one of the witnesses. What's that about?

ER: Well, a prosecutor is allowed to give a witness immunity for things that they've done. For instance, if somebody's killed somebody or committed a robbery or something, often they'll give one person immunity for ratting on the others. But a prosecutor is not allowed to give a person immunity for things that they will do in the future. They can't say, "Okay, this is a pass for killing one person. You get one free death." They can't do that.

So this fellow — Bob Martin — appeared as a witness for the prosecutors and then he continued his medical pot business. He even opened up a second dispensary. He was never bothered. He had a 100,000 square foot grove that was busted by the DEA, but no charges were ever filed. That happened in 2004.

So this guy has a free pass. Basically, each member of this conspiracy was getting something out of it. My prosecutor, George Beven was getting the information — or so-called information that he wanted. And Martin, who owns two dispensaries here in San Francisco, got a free pass. To me, that's a RICO relationship. And in this case, we don't have to show any paperwork, meetings, assignments or anything like that. We have actions that actually took place. So I'm initiating a civil suit against this action because their illegal enterprise has cost me a lot of money.

You know, I wasn't allowed to present these facts in either case. And the jurors were misled, because a half-truth isn't a truth. A half-truth is a lie. The jury was told that I had distributed this material, but they didn't hear that I had been told that I was free from prosecution.

That's an estoppel issue. Let me explain that. Let's say there's a red light, but a cop waves you through. Another cop, on the other side, can't give you a ticket for crossing the red light because you have been told that what you're doing was legal, right? You're following the cop's orders.

So I was told by the city attorney's office that what I was doing was legal and I was free from prosecution. So even if she was wrong, I should've been able to say to a jury, "Hey, look. I was led to believe that what I was doing was legal by an official." But the judge said, "No. Even though this person is a government official, she can't testify for you."

RU: The jury from the first trial was outraged after your conviction when they found out what was actually going on. That was very unusual. Describe what happened with the jury after the trial.

ER: (Medical marijuana activist) Hillary McQuie actually met with the first jury as they came out from the courtroom after the trial. And she told them that she thought they had made a terrible mistake and that they should look the case up. They did. They found out the truth. They were all dismayed and started calling newspapers. Eight out of the 12 jurors, plus one of the two alternates agreed that an injustice had been done.

RU: I remember when they were in the news, but I can't remember — did they actually petition the court, or did they release a statement? I remember they were active about their unhappiness.

ER: Three of them became activists for a while, and it changed all of their lives. They learned that they couldn't trust the government.

You know, the judge was very upset this time when we said we weren't going to present a defense. But we said, "We have no witnesses left. You've eliminated all our witnesses." He looked down at his list and he realized he'd eliminated everybody except for my wife and myself. So he said, "Well, I'll tell you what. I'll let you say anything you want to the jury. I'll let you talk to the jury, unimpeded. I'm not going to say anything to the jury while you're talking. I'm not going to interrupt you." And I said, "Okay, that sounds pretty good, but I want corroborating witnesses." And he said, "Oh no, I'm not going to allow you to have your corroborating witnesses." I said, "Well, you're going to allow me to give my theory of the case, but your not allowing me to corroborate it. This is insane." And I basically said that I was not going to play the game in his Stalinist show trial. I wouldn't be a part of it. The entire transcript is online at the Green-Aid website.

RU: Do you think you could've swayed the jury if you had testified?

ER: If I had testified and been allowed one witness, that would've been it.

STEVE ROBLES: Without the witnesses, the jury would just think you're some kind of nutter. The jury will be sitting there thinking, "Why didn't I hear a witness? Why couldn't this guy back it up?"

RU: Well, he could explain that. Weren't you really able to give your full story, including your objection to...

ER: No, not at all. And I'm appealing this. And anybody who's listening to this who has $100,000 that they'd like to spend on a court case, just get in touch with Green Aid. It's all tax deductible.

Win or lose, this case has made it apparent that the federal laws have to change, and that we need the Peter McWilliams "Truth in Trials" act. That act would let you use a state medical marijuana law in your defense in a federal case. It also indicates that the State of California has to start protecting the providers, because there are now over 100 providers who have been arrested and charged. Dozens are in jail and there are over 100 under indictment right now. And the only difference between them and me is that I'm a little more notorious or famous, and I have perhaps a little more media savvy than they do. Most of them are going to wind up doing time. And very often they say to the person who runs the medical marijuana operation, "If you don't plead to a long term, we're going to take all your workers and give them each five years."

RU: What is the next stage of your appeal? Where does it go?

ER: We're preparing our appeal to the 9th Circuit.

RU: You already went through the 9th Circuit once, didn't you?

ER: Yeah. We're asking for a new trial, and if not, we're appealing. We have a number of new grounds to appeal. I mean, these colloquies that I had with the judge were very unusual. You wouldn't believe what our conversations were. And they're all on transcript.

SR: It's the same judge again?

ER: It's the same judge. And, you know, people think he's a really nice guy because he only sentenced me to a day. But first, he took away my constitutional rights. And he only gave me a day because it was well publicized and it was looking really bad. But he regularly gives people five years, ten years, seven years, all the time. And he has a reputation for not letting defenses prove their cases.

RU: In going before the 9th Circuit court before, you got the case thrown out but it was basically on a technicality. You didn't really accomplish a mission in terms of having a positive effect on people who grown medical marijuana. Do you have an approach for trying to have an effect the next time you go before the 9th Circuit?

ER: Winning. But win or lose, I think that the policies are going to change, because the state is going to realize that they have to intervene. And also, there's more impetus for the Peter McWilliams "Truth in Trials" act.

RU: Is this something that's before the House of Representatives?

ER: Yes.

RU: How could California be counted on now to confront the U.S. Government? Schwarzenegger, who sort of played at being libertarian on his way into the governorship, has been a drug warrior through and through since he's been in office.

ER: Well, he's been trying to free himself from the power of the Corrections Department bureaucracy and the prison guards union. And he's found out that he can't do it.

RU: Right. That group basically owned Gray Davis.

ER: The Democrats have to get away from that. And there are incremental steps the system can take. For instance, police need to continually get credits for learning new techniques and stuff like that. One of the places where they can get this credit is through the California Narcotics Officers Association. So they pay for these courses where they're miseducated. Right on the homepage of the CNOA website, it says, "We believe medical marijuana is a myth." That's what they teach officers.

RU: These are people who are supposed to be enforcing California law, which approves medical marijuana.

ER: Other things need to change, For instance, in Oakland, the local narcotics officers work out of the DEA office in the Federal Building. They're cross-deputized. They're paid by the city, but they also function as a federal official. So the city needs to keep them separate.

SR: Some activists think that one of the big problems is Proposition 215. People think it's a hastily put-together proposition. It's swiss cheese — full of holes. They think the state needs to pass something a lot more substantive.

ER: I don't really think that's the issue. Look, marijuana is more popular than any politician. It wins by a higher percentage than politicians do. I'll give you an example. Bush won in Montana in 2004. But marijuana won there by a much higher margin than he did.

RU: People are getting stoned and voting for Bush!

ER: So there's a disconnect between the politicians and the voters on this. And the voters consistently say, "We do want these dispensaries. We want easy access." But the politicians are in the hands of the criminal justice system — the cops, the judges, the prosecutors. It’s such a big financial interest that nobody wants to let it go. We now spend more on jails than on higher education. We have a thousand people in California prisons for marijuana.

My suggestion is that we take this on a very local level – at the level of the councilperson. It's got to be city-by-city and they've got to push back the police.

Do you remember when Proposition 36 passed?

RU: Right. The idea was that people shouldn't go to jail for drug possession.

ER: Right — not for the first or second offense. So it passed, but then – first of all, the criminal justice establishment wanted to tighten it up. And if you go online and find all the arguments against it, they're all from people who are part of the criminal justice system.

See — if marijuana was legal and other drugs were treated with a harm reduction strategy, a huge bureaucracy would be eliminated – and a lot of jobs. There are 750,000 arrests a year for marijuana in the U.S. 88% of those are for personal use. That's about 5% of the entire criminal justice arrests throughout the United States. And it's an upward funnel, because when you get to second and third offenses, the sentencing for marijuana is much higher than the sentencing for violent offenses. So you have people spending more time in prison. Also, when they get out, they need social services, another bureaucracy.

RU: But doesn't this all have to be changed through the federal government, since they come in and shut down local medical marijuana and so forth? And if pot is more popular than politicians, why don't people make the politicians take their side?

ER: It's not necessarily a primary issue with most voters. Also, the criminal justice system can provide a potent opposition to politicians. If the Police Benevolent Association and the local police union says the politician is "soft on crime," that can be trouble. So a lot of politicians are cowed.

You wind up with people like Judge Breyer. Breyer knows that pot isn't a harmful substance, but he sentences people to prison for it. He's a war criminal! When you send somebody to prison, it doesn't just affect them. It affects their families. It affects their employers or employees. A whole community of people is affected.

RU: These are acts of destruction that are woven so deeply into the system that people don't even see them as being acts of destruction.

ER: Yeah! I don't know if you heard about some of my antics, but outside the courtroom I would say nasty things to the prosecutor. For instance, I called him a liar, because the judge found that he lied to the grand jury (but said no harm had been done). I called him vindictive. I called him a coward. So he went and complained to the judge about it. And the judge said, "Well, we all should be very civil and polite here." Meanwhile, they're putting one person after another in jail for providing people with marijuana. It's outrageous! How can they say that?

So the judge talked to my lawyer and said, "Can you try and control your client?" And my lawyer said to him, "Well, judge — perhaps it's my fault. I did advise him not to say anything nasty in the courtroom. But I didn't say anything about the hallway." So the judge said, "Oh, well, please speak with Mr. Rosenthal about this." But he also said something like: "This is in a federal building, but we may have First Amendment issues." So after this exchange, I went up to the microphone at the podium, unasked, and I said, "Your honor, I'd like to thank you for protecting my First Amendment right to call this man a coward, a liar, and vindictive. But I left something out. He's also a tattle-tale and a cry baby."

JEFF DIEHL: Does the "three strikes" law relate to these two marijuana convictions?

ER: I now have three non-violent felony strikes. You get into a fight with me; I'm away for life.

RU: All right, so, be gentle with me, man.

SR: Keep away from Terence Hallinan (ed: Rowdy pro-pot former DA of San Francisco.) because that guy's a maniac.

RU: So a lot of people think there are no consequences for you because the judge only sentenced you to one day. But all those felonies – those are big consequences.

On your site, there's a mention that you might be working on a book about pot legalization. What's your favorite method of legal distribution? Do you think it should be any way people want? Or should it be in specialty shops or liquor stores? Or should it be only homegrown? Do you have a favorite procedure for doing it?

ER: I see the tomato model. Let me explain. Home gardeners grow more tomatoes than are grown commercially. But there's also a gigantic commercial market for tomatoes. Some of them are served in restaurants. Some of them are canned, dried, served in different ways. So there are lots of different commercial ways that tomatoes are distributed. I see something like that. I don't think that it's ever going to be restriction-free. I think that there's going to be the same kind of civil regulation that we have with alcohol and tobacco. There are going to be taxes on it. But I think that many more people are going to grow their own than make their own beer or wine or grow their own tobacco. I think people are going to have all of those models. In terms of buying product, I think it'll mainly be through specialty shops.

RU: So, how soon?

ER: Well, in Oakland, we have Prop Z, which says that it should be able to be sold in private clubs.

SR: In California, within 5-7 years.

RU: Before I let you go, tell us about your new book, The Big Book of Buds, Vol. 3. You told us you have some new information in there.

ER: I have a piece in their about terpenes. Terpenes are the odor parts of flowers. Almost all flowers that produce odors have terpenes. It's four simple molecules, but there's a lot going on in the way they're assembled – like with DNA. So the structure of assembly of the terpenes creates all the different odors. So I used to say that the reason why different marijuanas give you different highs is because they have different recipes of cannabinoids – somehow one will have a little more CBD or a little more CBL or other cannabinoids. But it's been shown that most modern marijuana has a big spike of THC and hardly any other cannabinoids. So the question is: what else causes different types of marijuana to give you different highs? It comes down to the terpenes. And it's in the odor qualities of cannabis.

See also:

The Simpsons On Drugs: 6 Trippiest Scenes

Prescription Ecstasy and Other Pipe Dreams

Willie Nelson's Narcotic Shrooms

Paul McCartney On Drugs

Hallucinogenic Weapons

.jpg)

Their name is "Perverted Justice" — and something strange happens when you follow hyperlinks to their site from Wikipedia.

Their name is "Perverted Justice" — and something strange happens when you follow hyperlinks to their site from Wikipedia.

1: John Wayne

1: John Wayne 2: James Bond

2: James Bond 3: Hemingway

3: Hemingway 4: Jason Bourne

4: Jason Bourne 5: Harry Potter

5: Harry Potter 6: Brad Pitt

6: Brad Pitt 7: Barack Obama

7: Barack Obama 8: Anderson Cooper

8: Anderson Cooper 9: Danny Tanner

9: Danny Tanner 10: Mr. Sensitive

10: Mr. Sensitive

10 Zen Monkeys received the following document from a friend who works as an aide to Republican Louisiana Senator David Vitter. It is the handwritten draft of the statement Senator Vitter planned to give before the press conference about his involvement in

10 Zen Monkeys received the following document from a friend who works as an aide to Republican Louisiana Senator David Vitter. It is the handwritten draft of the statement Senator Vitter planned to give before the press conference about his involvement in

Yolanda is happy with the relationship, but she’s starting to want more. Her CD is starting to shrink, but she does not sense the same happening with Howard. So she begins to Pull (III) on Howard’s CD, dropping hints about rings and babies and puppies. She begins buying toothbrushes and storing them in random nooks of Howard’s house. Howard notices this behavior, and subconsciously begins to push back, trying to lengthen Yolanda’s CD to match his own. He stops returning her calls as quickly and leaves copies of Playboy out in his bathroom. (See Fig. 1.)

Yolanda is happy with the relationship, but she’s starting to want more. Her CD is starting to shrink, but she does not sense the same happening with Howard. So she begins to Pull (III) on Howard’s CD, dropping hints about rings and babies and puppies. She begins buying toothbrushes and storing them in random nooks of Howard’s house. Howard notices this behavior, and subconsciously begins to push back, trying to lengthen Yolanda’s CD to match his own. He stops returning her calls as quickly and leaves copies of Playboy out in his bathroom. (See Fig. 1.)

.jpg)