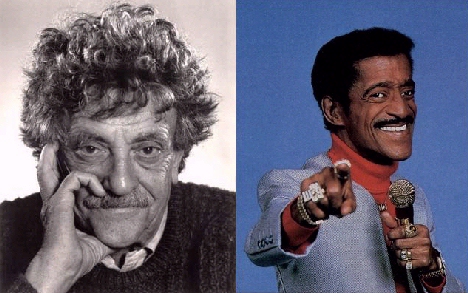

When Kurt Vonnegut published Slaughterhouse Five, he was 47. He'd struggled for 20 years to earn a living as an American writer, working as a public relations man for General Electric, an advertising copy writer, and even a car salesman. "All I wanted to do was support my family," Vonnegut wrote in 1999. "I didn't think I would amount to a hill of beans."

But this forgotten period of his life also includes a haunting story about television, a World War II story, and Sammy Davis Jr.

With two children, "I needed more money than GE would pay me," Vonnegut wrote in his introduction to Bagombo Snuff Box: Uncollected Short Fiction. "I also wanted, if possible, more self-respect." Vonnegut hoped to spend his life writing short stories for magazines, and began tapping his experiences in World War II — and in the world that followed. But in the 1950s the magazines publishing his fiction were exterminated by the ultimate juggernaut: television.

"You can't fight progress," Vonnegut wrote bitterly. "The best you can do is ignore it, until it finally takes your livelihood and self-respect away." In 1958 his sister died — and then her husband a few days later — and the 36-year-old would consider abandoning writing altogether.

In another world, Sammy Davis Jr. was a rising star. Though the 32-year-old had yet to join Frank Sinatra's Rat Pack, he was making a name for himself as an entertainer in Las Vegas and on Broadway. In a 1989 biography, Sammy remembered asking his agency for a role in TV dramas, and being told a black actor would be too jarring for audiences in the south.

"Baby," he replied, "have you any idea how jarring it must be for about five million colored kids who sit in front of their TV sets hour after hour and they almost never see anybody who looks like them? It's like they and their families and their friends just plain don't exist."

Sammy's genuine pain found echoes in one of Vonnegut's stories. D.P. — published in Welcome to the Monkey House — tells the story of the only black boy in a German orphanage. ("Had the children not been kept there...they might have wandered off the edges of the earth, searching for parents who had long ago stopped searching for them.") When the boy spots a black American soldier, he mistakes him for his father.

Sammy was cast as the soldier in a television adaptation of the story. Though TV was killing Vonnegut's career, he'd ended up as the co-author on this single teleplay. (Ironically, it was to appear in a showcase of half-hour dramas sponsored by his old employer: G.E. Theatre.) The published story ends with the young boy explaining his newfound hopes to the other skeptical orphans.

"How do you know he wasn't fooling you?"

"Because he cried when he left me."

In the teleplay, the heart-wrenching scene is played out. The alienated soldier — an orphan himself — finds himself abandoning the boy, yelling "Go away! I'm not your father!

"I don't need you!"

Then he realizes he can't do it. He collapses to his knees, and sobs "I need you."

And he promises he'll be back.

Sammy remembers that "everybody on the set was crying." Future President Ronald Reagan even wandered in — then the host of GE Theatre — and said warmly that "It's going to be a wonderful episode."

And according to Sammy's biography, his Hollywood agent Sy thought it was a milestone for America. "Well, sweetheart, you've made television history. When they write the books about the tube, they've got to write that Sammy Davis Jr. was the first Negro actor to star in episodic television... You'll have opened those doors for others to follow." Sammy remembered that "It didn't matter what as long as they broke out of it being just maids and butlers."

But there was one problem. General Electric worried that nearly two-thirds of their products were sold "below the Mason-Dixon line," according to Sammy's agent. His biography remembers that painful conversation. "They say they will be ostracized by their white customers and dealers. So there's no way we can use that show.

"The sponsor is the boss... GE paid for the show, and it's GE's right to bury it."

The show finally aired — in a doomed time slot competing against Rock Hudson's first television appearance ever. But surprisingly, it beat Hudson's ratings in New York, Chicago, Philadelphia, and Los Angeles — and was only a half point behind nationwide. The reaction was surprisingly positive, and GE even cast Sammy in two more episodes. And somewhere, America began to change.

Before publishing SlaughterHouse Five, Vonnegut struggled through another 10 years of writing. In Bagombo Snuff Box he complained that when he published Mother Night and The Sirens of Titan, "I got for each of them what I used to get for a short story."

But eight years before his death he'd look back fondly on the 1950s in America, remembering it as "a golden age of magazine fiction..."

"...a time before there was television, when an author might support a family by writing stories that satisfied uncritical readers of magazines, and earning thereby enough free time in which to write serious novels.

"This old man's hope has to be that some of his earliest tales, for all their mildness and innocence and clumsiness, may, in these coarse times, still entertain."

See also:

Robert Anton Wilson 1932-2007

Neil Gaiman Has Lost His Clothes

Rudy Rucker Interview

When Cory Doctorow Ruled the World

Hmmm… I guess that would make 6 degrees of separation between Sammy Davis Jr., Kurt Vonnegut, Ronald Reagan, an Anton LaVey. (Oh sorry….make that 666 degrees…) Just wondering what THAT conversation would’ve been like. Probably would make for a good book.