I always sort of liked Timothy Leary, but I never took many drugs and never really read any of his work. I've sat through a few videos in which he came off as a good-natured eccentric — spaced out, but with a sharp sense of humor.

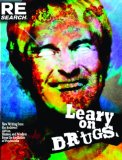

This book is a surprise. Published by Re/Search, purveyors of books about pranks, punk rock, and body modification, it may not make you want to become an "enlightened" acidhead, but it should leave you with at least one insight: Timothy Leary was a damn fine writer. Who knew?

I interviewed Leary On Drugs editor, Hassan I Sirius, by email to get the scoop on this new collection of Leary's writing.

| Click here for more information about the book! |

JAYDEN DEVEREUX: I was mostly surprised by the quality of Leary's writing and his seriousness of purpose. How did you go about selecting materials for the book?

HASSAN I SIRIUS: My approach was pretty much exactly what you've just implied. Most of the content was selected for the quality of the writing and for the calm lucidity of Leary's thoughts about drugs. With all the recent positive reports about psychedelic research (Time magazine even had a story titled "Was Timothy Leary Right?") — and with the growing awareness of the destructive nature of drug prohibition, it seemed wise to try to make this a fairly serious contribution to our collective knowledge and thinking regarding drugs, particularly of the psychedelic variety.

Leary wrote a lot of material, some of it frivolous, some of it caught up in the battles and in the hype of a particular time period. And some of that material may not stand up to scrutiny. I think I mostly selected materials that stand on their own. You don't have to understand the sixties or the seventies all that well to get something out of these pieces. They really are pretty much focused on drugs – descriptions of experiences and visions, theories, observations and so forth.

JD: The theoretical material is a bit dense. He had a scientific orientation.

HIS: Yeah. Even when he was living in a teepee at the height of the hippie movement, he never cancelled his subscription to Scientific American. And even though he started using all those eastern Hindu metaphors that became so popular then, he was also seeing it all in terms of genetics and DNA, very early on. It was not that long after the discovery of DNA – less than a decade — and this really impacted on his vision of psychedelic experiences from the start in 1960. You can pretty much find him intuiting evolutionary psychology even in his earlier writings. He went on evolutionary trips, experiencing the emergence of life and its evolution toward humanity. He assumed everybody would have that trip, which is one place where he went a bit astray.

JD: I was able to understand most of it. Most of his arguments for psychedelics don't seem particularly wild. But what I really enjoyed was the stories. Some of those are pretty wild and pretty intense. The political section is almost scary. Can you say a bit about that?

HIS: Yeah, well some of the trip stories are pretty intense too. But you're probably referring to the story involving Mary Pinchot, who was one of President Kennedy's lovers. And it seems pretty clear that she involved Leary in a successful conspiracy to turn JFK on to LSD. The material, in this case, is from his autobiography, Flashbacks. But in Flashbacks, this particular narrative was sprinkled throughout the book as you go through his life chronologically. When you actually isolate the sections about Pinchot and then stitch them together as an entry, it makes a stronger impression.

The other thing you may be referring to is the conversation at the end of the book that Leary had with a hardball Swiss political operative with various intelligence connections while he was in exile from the U.S. government in Switzerland. The entry is almost painful in its sophistication and leaves the book on a solemn note — we are still all prisoners of men who lust for power, from Leary's point of view.

JD: What were Leary's favorite drugs?

HIS: I guess they all had their place. He was a social drinker and he was a social guy… so that amounted to a fair amount of drinking. It's sort of funny – he's always celebrating great moments in the psychedelic revolution with a glass of champagne or something along those lines. Mind you, I don't see anything wrong with it. And he always thought LSD was an extraordinarily marvelous invention. In a 1988 article included in the book, he writes about "good old LSD" and marvels that it's still the best. There's a segment on heroin. He wasn't crazy about heroin, even though he found it pleasant when he tried it… and he makes it clear that he wasn't happy about the dominance of coke and crack in the drug culture during the 1980s.

JD: Do you think he would be happy with all of the psychedelic research going on now?

HIS: He was alive to see it begin again and he commented on it favorably. Yeah, he would be thrilled with the positive reports. People forget he started out examining these drugs in a therapeutic context. On the other hand, he denounced control of drugs by the medical profession, particularly later in his life. He took a libertarian view that adults have a human right to do what they want with their brains. But at other points, it's clear that he prefers the medical model to leaving it in the hands of the drug warriors.

JD: So what does Leary have to say to us now?

HIS: Well, read the book. It's not so much reflective of the politics of the moment – although plenty of lessons about that can be found in there — but most of the material is really reflective of a search for meaning, and self-understanding, and peak experiences that people can find valuable no matter what is going on in the world.

In this book, what you get, mostly, is a very thoughtful and sensitive Leary pondering the meaning of it all.

See Also:

Prescription Ecstasy and Other Pipe Dreams

Hallucinogenic Weapons: The Other Chemical Warfare

Counterculture and the Tech Revolution

Don't Call It a Conspiracy: The Kennedy Brothers

The founder of PayPal just gave "mad scientist"

The founder of PayPal just gave "mad scientist"