Editor's note: We experienced some hesitation at publishing this piece. We know that people have strong emotions about these topics and, obviously, the sexual abuse of children is no trivial matter.

But given the players, including the New York Times, the Justice Department, the Internet, and Free Speech itself, we feel confident that it will start an important debate on a number of issues that are usually dominated by hysterical, reactionary voices.

For a free month's subscription to "In Bed With Susie Bright," click here. Links to the full audio versions of this interview can be found here: Part 1, Part 2.

Debbie Nathan is the expert on sex panics and is perhaps best known for her book,

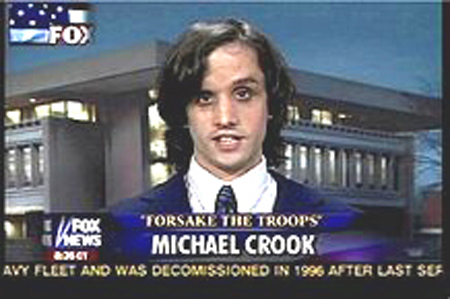

Satan's Silence: Ritual Abuse and the Making of a Modern American Witch Hunt, about some of the widely covered sex panic cases that rocked the U.S. in the '80s and '90s, such as the McMartin preschool case in California. Susie and Debbie share a deep distrust about former

New York Times journalist Kurt Eichenwald's much talked about articles on Internet child pornography.

SUSIE BRIGHT: First of all, you uncovered the bizarre so-called "satanic abuse

scandals" that were happening in Southern California in the 1980s,

and I remember thinking, "How could people re-create the Salem witch

trials in this day and age?" And the next time you popped up in my

life, I was reading these sensational stories in the

New

York Times about child pornography,

which the reporter described in amazing, titillating detail — and of course he was on a campaign to stop it.

Nevertheless, I put down the newspaper I was reading, and I

thought, "How does this guy get to look at anything that is remotely like

'child pornography' when the whole genre is utterly and completely illegal in the United States? What is the deal... Did he do a deal with the

Justice Department? And what are

they showing him?" And, "How come he doesn't talk about any of this?"

(Ed: Former New York Times reporter Kurt Eichenwald has denied ever looking at illegal pornographic images.) The very next day,

there's an article in Salon — by you, Debbie Nathan. And it had this

provocative title,

Why I Need To See Child Porn.

DN: And then the next day, it was gone.

SB: And then the next day, it was gone! Because the reporter who'd

written the original piece just blew his stack and

threatened Salon

with legal action if they didn't take this piece down. Well, I want to get back to your rebuttal — the very first thing you said, which is: If child porn is such an

immoral outrage, then why does anyone need to look at it? Why is it anybody's business?

Aren't we just supposed to say, "My god, that's aberrant," and turn our

heads away?

DN: Well, there are two reasons for that, and I'm not sure which one is more

important. But the first one has to do with technology. It has to do

with the fact that in this country — not all countries, but in the United

States where we respect the First Amendment — the reasoning behind outlawing

child pornography is that it is the record of the

victimization of a real child.

SB: The photographic record.

DN: The photographic record. Now, we don't outlaw

photographic records of other crimes. For example, we didn't outlaw

looking at the Abu Ghraib torture pictures...

SB: Boy, I'll say.

DN: ...which were sexual tortures. But we do outlaw looking at

photographic records of sexual crimes against children. Now, of course, that brings up a whole other can

of worms, which is that a lot of child pornography involves 17-year-olds or 16-year-

olds. It used to be that you could make pornography in this country if

you were over 16.

SB: How recent was that?

DN: You know, I can't tell you

the exact year, but it seems to me that it was changed in the 80s. It

might've been the late 70s. But the age of model consent used to be lower than it is now. So then you get into

the whole argument and controversy about what is a child? We have statutory definitions, but in the real world, I think

we know that there's a huge variation in emotional development.

SB: Let's say it's non-consensual, it's basically rape on camera. You know, there'd be no

question that everyone would be horrified.

DN: Let's say an 8-year-old who's being raped. Okay?

SB: Oh, god. Okay... Why does anybody need to scrutinize that, aside from the Department

of Justice?

DN: I still haven't even finished my first point. And my

first point about the technology is that it might not be a real child.

Because we now have morphing. We have ways to take pictures of adults, for example, and fiddle around with pixels in Photoshop. We have ways to make adults look

like children. You can actually make a young adult look like

an 8-year-old. You can do cartoons.

SB: This is reminding me of when I

was a good Catholic, and we discussed venal sin. There, somebody

might say, "Okay. So you didn't really do this. But you

thought

it."

DN: You thought about it! That's right.

SB: "And we should lock you up forever and chop your balls off for even

thinking about this!"

DN: Yeah, — well, that's where we're at. Now we've got

the technology to produce sexualized representations of children where

there's no children. So it's not a record of the exploitation of

anyone. It's just a piece of art. You might consider it tasteless and

repulsive, but it's just a representation and it's not a representation of reality. Now

in this country, that is not illegal. In other countries it is, but not

in the United States. So how do we know what's on the internet? This is

question #1. The government goes around saying there's a tremendous

amount of child pornography on the internet. No one really knows how

much of it is photographic records of real crimes against real

children and how much of it is morphing imagery. So that's question #1.

How much illegal stuff is on the web? We don't know.

People need to know. And somebody needs to be able to look at that

stuff who's not in the Department of Justice, because they've got their

own agenda.

SB: At this point, the Department of Justice's reputation is so bad, I

wouldn't give them authority to walk across the street.

DN: The thing is, this is the last frontier of authority

for the Justice Department. And that's the second point — not only do we not know how prevalent child pornography really is, the government is claiming that it's a multi-billion dollar industry and it's huge. And they're now using that claim

to justify the Patriot Act.

And we all know Gonzales is in big shit right now because of a bunch of

things including illegal use of the Patriot Act and the firing of

all of these attorneys. So he's trying to divert

attention by saying, "Well,

I'm not so concerned about all that because I'm

still following my agenda, which is to attack this

terrible problem of child pornography on the internet."

And when the DOJ puts this stuff out, nobody makes a

peep. Because this country, this culture, is so ready to believe

anything that the government says about child pornography. And that's

why you need people outside of the government to be able to look around on

the internet. No one has any idea what's really on the internet

except maybe — you know, the FBI. Although I'm not sure what they know either. But they're very

quick to make claims. And that's dangerous!

SB: Well, when it comes to how to get at the perpetrators of child

abuse, why isn't the law completely focused on the criminal act, as it

happened, as opposed to whatever record there is of it?

DN: Well, the DOJ will tell you that it's very hard to go

backwards and find the child. I mean, there are a lot

of people in the world who like to look at representations of children

having sex. And most of them, it turns out, never touch kids. It's just

like most of the sort of more far-out pornography — people

don't do the stuff that they look at. You know? And that's true,

apparently, with people who like looking at child pornography. They

never touch kids. So there is a lot of stuff out there that's consumed

by people who don't touch kids, and the government claims that they can't go back and they can't find the kids.

But the government also makes this argument, which is completely

specious in terms of any research, that child pornography causes or

incites people to molest children. There's no evidence for that

whatsoever.

SB: Maybe I should get to the big picture question behind a lot of

this — the notion of sexually taking advantage of an

innocent. Child porn boils down to

the ultimate taboo. The ultimate "big picking on little" —

sometimes the incestuous thing is brought into it — the notion of

somebody who has all the power taking advantage of someone who has nothing.

It is a classic, epic taboo. Yet, if it's so taboo, then why do we hear

about it all the time as if it was a tuna fish sandwich? I mean, how do those two things reconcile? Something that cannot

be spoken — unspeakable, makes people's stomachs turn. And yet, oh —

child porn here, child porn there, kiddie porn, massive billions. You

know, where is the truth in those two completely opposite pictures?

DN: I think they go together. Censorship goes together

with the proliferation of porn and this incredible fascination with

porn. But it's even moreso with child porn. And, you know what's

interesting, Susie — if you look cross-culturally, and you go way back

in history, you'll see that whenever a culture is worried about

something, or feeling guilty, it puts kids up as a symbol of the ultimate

innocence of the culture. And it also posits kids as the symbol of its

future. So if it's worried about the future, and it

feels culpable — then people just really zero in on the endangered

child. And then you combine that with Western, and

particularly modern Western fears, since the last couple

hundred years of sexuality — and you get this incredibly potent,

overloaded symbol in the sexually abused child. And also, over the last couple of generations,

there's the increasing use of sexuality as a consumer god.

SB: My own political roots are as a feminist. And part of the

way feminists changed public conversation was to say, "You know what?

Next time people start blithering about the plight of women and

children..." — and of course, they're always put together. They're

infantilized together — "...we're going to take a different tack. We're

going to talk about this differently. Not just for women's sake, but

also for children's sake." And I was wondering — you're a feminist. What do you think would be a healthy way for anyone to discuss young people's sexuality — whether they are children

or teenagers?

DN: I highly recommend a book by one of my good friends, Judith

Levine, which is called

Harmful to Minors: The Perils of Protecting Children from Sex. It's a wonderful book about

the fact that children really do have sexuality. Children are not

"innocent" in the way that term is used in our culture. And how do

you deal with children's emerging sexuality? Well, I think the first

thing you have to do is acknowledge it. The second thing you have to do

is teach kids how to own their own sexuality, and I think you start that

immediately. Children are conscious human beings

from the time that they're born. But of course in this country, we

have this complete crisis — this total attack on sex

education. So the first thing you have to do is have a national conversation about the fact that

children are sexual beings.

That's a Freudian idea that's completely out of style now. And I'm not saying Freud should come back, but the actual baby got thrown out with the bath water when people started critiquing Freud.

SB: That's ironic, isn't it? In some ways,

I was part of the rejection of Freud that went on during early feminism. But

we had our own version of claiming one's sexuality, as the rhetoric

put it, which had a lot to do with masturbation, and the idea that this is

your body, it's yours to decide — your virginity does not belong to

somebody, it can't be sold to the highest bidder. You know, it's not

something that your father is protecting, to

hand to another man in marriage. All those kind of ideas were getting

the big heave-ho with the notion that you have your own sex stuff. It

belongs to you. And I don't see

that kind of consciousness being very popular today. It's more like, oh, you're growing up? You're starting to come into

your own? Well, how can you look sexual? And then, how can you pitch

that look to your advantage? That is what I notice

in popular culture now.

DN: That was

certainly true when I was a teenager.

I think it's gotten exacerbated because every year consumerism becomes more

powerful. People express themselves more and more

through consumption, through commodity consumption. And sex has been

colonized by —

SB: The aliens?

DN: ...by the aliens who make all these commodities! Whether it's

clothes or makeup. 15-year-olds who are virgins

are now getting Brazillian waxed. It's like, every single part

of the body and every form of expression is being colonized by the idea

that you've got to buy something. And sex is the way that you convince

people to buy things. Because, you know, you terrorize people by

thinking that if you don't buy this product, you're not going to be

sexy!

SB: When the words "child porn" or "kiddie porn" are referred to

as a business or some sort of industry that's in progress — I

feel a little suspicious. Because there are millions of kids around the

world who are being used as slaves, basically — they're forced to work in a factory, or in someone's home. Or just sweat labor. And they have no out. They have no passport. They

have no wages. Nothing. This is monumental. And

certainly, I wouldn't be the least bit surprised, considering they have

so little power, they might be sexually exploited at many ends of their

situation. But it is not a child porn business, per se. It is an

"exploiting children" business — it's got a lot

tentacles, it goes in every direction. It's not like it's a cut-out.

Do you know what I mean?

DN: Absolutely. Anyone who has spent any time in a poor country

knows that there's a continuum of exploitation.

Everyone is exploited, and kids go to work

early. Kids go to work in a country like Mexico, working

class kids, when they're 8 or 10 or 12 years old. And they can be

working in a factory for $4 a day. They can be out on the

street selling pumpkin seeds for $5 a day, or they can be in a red light

district for $50 a day. So, for women in

the third world, it's more lucrative to do sex work. And I've talked to

poor women and to poor children. They don't even consider themselves

children any more! You know? They're out working by the time they're

ten years old. So in their minds, they're not children. They're

contributing to the livelihood of their families. They have

"agency" — that's that word that sociologists use. They will

sit and talk to you — they're very rationale, in their own

10-year-old, or 12-year-old, or 15-year-old way. They've figured out how to support their families the same way that

older women try to figure out how to support their families. And, you

know, it's a political/economic problem. It's not, to my mind, a moral

problem. Unfortunately, the sad thing is no one cares about girls who work in

factories. And no one cares about girls who sell pumpkin seeds. And no

one cares about women who work in factories.

I wrote a piece

in

The Nation a couple years ago suggesting that there was far more

slavery in this country involving non-sex work. (Actually, two years

or three years after I wrote that piece, the

Government Accounting Office has just released a study

suggesting that's probably right.)

It was a very controversial piece. And the biggest attacks

I got were from self-described feminists who want all prostitution to be

defined as slavery, even when it's voluntary. So it's very hard to get people

excited about people being forced to pick broccoli in a field, but they

will get really excited about the idea of sex slaves. It sounds

prurient. It gets people excited. It's another one of those S&M

fantasies.

SB: You have a new book out called

Pornography , and it's part of a

learning series for young adults to grapple with issues of the day, but

it's a good primer for anyone who might want to look at some of

the basic arguments about porn. And what amazes me is, when it comes to the huge majority of porn that is

produced and consumed, it is the same banal sucking and fucking over and

over and over again that dominates the market.

DN: I think the stories that you hear in the

media, the gloom-and-doom, scary stories about the bukkake

and the donkeys — that's all coming from the so-called

clinical samples. That's coming from the people that are in therapy because they consider

themselves to be porn addicts, and they've spent all their time

finding the weirder and weirder stuff. That's the story, right? "I

lost control of it. I wanted to see weirder and weirder and weirder

stuff." And that's the porn consumer in the popular

imagination now.

SB: I totally reject the notion that that's the cycle. Most people

don't sit around with their porn having to have more and more and more

extreme...

DN: No, but that's the clinical tale. That's the tale that the

media likes, because it's the scary tale.

SB: Well, it's funny you should call it "clinical." Because it's not

even accepted by most of the psychiatric profession. There is no such

thing as porn addiction in the DSM manual.

DN: I know. And if you look in my book, you'll see that

I debunk that. But that's

the story the mass media likes to tell. That's

what they hang the problem on — the weirdo stuff.

SB: Explain that, because people

hear this all the time. "Are you a porn addict? Are you going to

become addicted to porn?" Why is that an inappropriate word to use?

DN: Addiction is a

physical thing, like nicotine is an addiction, and alcohol is an

addiction, and heroin is an addiction. These are things

that your body becomes physically dependent on.

And people reject the use of the word "addiction" for things like brushing

your teeth, or as Leonore Tiefer puts it, "spending too much time reading

the New York Times."

SB: Guilty!

DN: Or spending too much time at work, which is a huge

problem. Or spending too much time, in your own estimate, watching sports

on TV. Or spending too much time in the garage, playing with your drills

and making boats in bottles. And now we have spending too much time

watching porn. These are just — as Leonore calls them — "bad habits."

SB: What's the difference between a bad habit, or maybe feeling

like, "Gosh, I really wasted too much time doing that," and what would

be diagnosed as obsessive-compulsive disorder?

DN: I think that's pretty subjective. I mean, if you look in

the DSM, it says most disorders have to do with whether the person feels

troubled by the behavior. Even if you look at pedophilia, the

definition of pedophilia is that you have an attraction to pre-pubertal

kids and it bothers you. If it doesn't bother you, then it's not a

disorder.

SB: What if it it bothers everyone else?

DN: Well, they wouldn't know if you didn't go out and act on it. If you

go out and act on it, then you're a child molester. But not all child

molesters are pedophiles, and not all pedophiles are child molesters.

The same thing with porn. Certainly, if you're the president of Vivid, and

you

have to look at 14 hours of porn a day to make your $300,000 a year, I

don't think anyone would call you a porn addict. That would be a useful

thing to be doing!

SB: What do you say to people who say, "Debbie, look! I personally

feel like I look at porn too much, and it's upsetting to me, and it's

upsetting my life."

DN: I'm not a therapist, but the therapist that I talked to for

the book said that...

SB: Don't they ask you anyways? They don't care whether you're a

therapist or not!

DN: They only call me the evil journalist who doesn't care about kids.

SB: But when you're not an evil journalist, I bet you get treated like a

shrink sometimes.

DN: Okay, so here's what the therapists say. They

take that very seriously. And what they say is, "We need to look at what the problems are in your life that are causing you to sooth yourself?"

They see looking at a lot of porn as a self-soothing activity,

in the way that many activities are self-soothing when you're anxious, or you're suffering from anxiety, or from depression. And so

they try to get the person to look at the behavior in terms of — "Why did

I decide to look at porn on the net instead of read

the

New York Times all day?" Or "Why did I decide to look at porn on the

net instead of watching too much basketball?" And if you really look at the meaning of your habits —

because everyone's a complicated individual, with a complicated,

intra-psychic past — you can come up with some pretty good

stories about yourself, and what your attraction is to this particular

self-soothing activity.

The therapists that I've talked to have

said, "If the person's depressed, you treat the person for

depression. If the person's anxious, you treat 'em for anxiety." And

you also work on trying to understand what the behavior is, and what the

fantasies are that lead to the behavior. And again, I mean,

it's a wonderful thing to explore your fantasies. And not all fantasies

have to do with pornography. Some of them do, some of them don't,

right? We need to understand all of our fantasies.

SB: I often say "sexual expression" rather than using

words like "pornography" or "eroticism." Because I'm so tired of all

the baggage those words carry.

DN: Well, Leonore Tiefer has a lot of patients who come in

complaining that they're addicted to pornography. And she

says, maybe the person started looking at pornography on the web because

he came from a very restrictive, strict background, and it's a way of

rebelling against an overly-strict authoritarian father. So then

the fantasy is not so much sexual as it is rebelling against that

father. Now, of course, you get a whole sexual overlay,

because the bad habit happens to be porn-viewing. But the real profound thing might be what happened in childhood with

the father that has nothing ostensibly to do with sex. People are just very complicated.

SB: Also, porn is typically discussed in terms of whether it's

harmful, or it's benign.

DN: Yeah, it's so utterly overloaded with moral stuff. And that makes

it even more troubling to people.

SB: I come from a place of saying, "Well, I'm an artist. And I'm

interested in including the sexual part of creativity in the work that I

publish or produce." And so it's not a matter of me deciding

whether something is harmful or benign. But rather, in an artistic work, a

creative work — sexuality is going to make all the difference in

understanding it — its pathos, or its comedy, or its tragedy. It's

hard to imagine a lot of the greatest artistic works that

people revere if you took the sexual element out of them. That

doesn't seem to get discussed in political debates.

DN: It's really weird that you just made that statement,

and juxtaposed it with this sort of really sad conversation

we're having about people in deep distress. You know?

Because your statement is a very joyful, aesthetic

statement, and what we just talked about is people coming in hating

themselves, feeling that they're evil and out of control. It's very sad.

And porn is just so completely overloaded with moralism that

the therapist that I spoke with said, "It's really hard to get people to

even think deeply about what their relationship is with it, when they're

in therapy and they come in with these complaints. Because they're so

ashamed!"

SB: Well, as a fellow professional journalist and a

researcher into this sort of thing, you have this tendency — like I do, to just throw yourself into the most volatile situations!

And then you say, "What's a nice girl like me doing in this anyway?"

DN: Yeah. It's really true. You've heard me

kvetching, haven't you?

(Laughs)

SB: Yeah, I have. But I understand it, because I often tell my

friends, "I'm so scared." You know, I took on this

monster. I've put myself right in the middle of it. And I can't handle

it. I can't handle it! And they're like — are you kidding?

DN: You know what it was with me, Susie? The first time I got involved with this — what I call sex

politics and sex panics around children — was with the Satanic daycare

panic.

SB: And did you know what you were getting into?

DN: No. I had a two-year-old when I first heard about the

Satanic daycare centers. I remember hearing about the

McMartin case. I

was sitting in a rocking chair, giving my kid something or

other — like maybe a bottle or a book. And on

the radio, they were talking about the little old lady at the McMartin

pre-school — the 80-year-old who killed rabbits while she brutalized

children sexually. And I believed this! I can remember sitting there

saying,

"Oh my god! Oh no! I can't send my kid to daycare..."

I can remember this so well. I thought, you know what? People will do

anything.

They're capable of anything. Well, then Ellen Willis, god bless her,

who just died last year, started

getting suspicious about this stuff. And she asked me if I looked into

McMartin. It's a long story, but

there was a case in my own community in El Paso, Texas. The first two

women to ever be convicted were in my little city. And I was

supposed to spend six weeks — but I spent eight months looking at

this case. And I had no idea what it was when I first started. But I was

just knowing that there's certain ways that kids act, and that

you probably wouldn't be able to put a 14-inch knife up a 2-year-

old's rectum...

SB: Oh, god!

DN: ...and then have the kid come back from daycare smiling and

telling you that he couldn't wait to get back the next day. You know?

SB: And yet those were the stories.

DN: Now do you need to have a two-year-old child to know that? I don't

know. But the thing is, I was a mom, and — you know what? I didn't

feel guilty about critiquing the believability of these cases. A lot of

the reporters back then were men, or they didn't have kids. And if they

would have asked any questions about those cases, people would have said, "You

don't care about kids."

SB: Or you're a pervert yourself.

DN: "You're a guy." You know? "You're a man, you're a pervert, you're

supporting the molesters..." Fortunately I was a woman and a mom. When I read the interviews of the kids, I could see the way the cases went forward forensically. The adult

interviewers, whether they were detectives or social workers or

psychologists, brainwashed the kids. They interjected

their own fantasies into those kids by asking them leading questions

over and over and over and over. I heard some of the tapes of kids who

would walk into the room loving their teachers. And they

would walk out utter basket cases, thinking that they'd been brutalized

by Miss Mickey or somebody that they loved before. And I

would cry. I would say — these kids have been brutalized by the

investigation and by this whole panic. So were the women that were

working in public daycare. That pained me to no end, the fact that

public child care was under such assault. And it pained me to see women

so guilty about going to work. But the thing that really got to

me was the fact that relationships that were really beautiful

were destroyed. You could hear it on the tapes. It was

horrible to hear those interviews. And then you're like, "Oh my god. I have to tell the world about this."

SB: Well now that you've seen and researched a number of these stories,

do you have any conclusions about what the seeds are for a sex panic?

Like, can you recognize certain things that are in play before it blows

up? Or is it still kind of unexpected when it happpens?

Some people said, after these daycare scandals were exposed, "This is to try to get women to be afraid of

using daycare." You know — an anti-child care plot. I thought,

well that's interesting, but how would anybody have

known that to begin with? What is it about a community where the

beginning of a Salem witch trial is just bobbing underneath the

surface?

DN: I cannot predict it. In fact, what's happening right now is a panic about kids and the internet. And there is a

panic about teenagers having sex with each other. Those two things are

working off each other. Did I predict those? No! I

didn't predict them. And it seems to be happening since 9/11, actually.

I think that the most proximate

thing is fear of the internet. There's always a panic over a new

technology. There are

moral panics all the time. I mean,

there was a moral panic over the telephone when it was first

introduced.

SB: That's right! Because strangers would call you...

DN: Yeah. Male voices would call up young women in their homes.

SB: And god knows what would happen from there.

DN: There was a panic about comic books. There's always a

panic about new technology.

We're looking at it in hindsight. We're looking at a

panic, and we're looking back and saying, "Oh, the internet."

SB: Oh yeah. Remember when that was such a big fright? And now it seems

like nothing. That's what always happens as soon as the technology

ages.

DN: But it's not nothing for a lot of people with kids today, you

know?

SB: Well, I had another interview on our show with a

social scientist named

Mike Males. And he has these great papers that

say, "Look, your kid statistically is in greater risk being in church or

at the shopping mall than they are on their MySpace page." The notion

of the actual risk that young people are facing on the internet is

completely blown out of proportion.

DN: Right. And are people going to listen to that? I mean, that's not

what a panic is about.

SB: They're going to, because I'm going to say it until I'm blue in the

face!

DN: That's right. Say it! Yes.

SB: The thing that gave you a little bit of liberty to speak out was the

fact that you were a woman and a mom, and people couldn't easily toss you aside and think you had bad motives. But have you

ever felt the sting from a different direction — people saying you're unfit to be a mother? How dare you speak about this? You know,

"You're crazy, you need to be discredited." How do you cope

with attacks from people trying to undermine you?

DN: When I was doing the daycare work, I

actually had the cops at my door.

SB: That must've been terrifying.

DN: It was pretty scary. Yeah. Back then I had little kids.

Now my kids are big, so nobody can use my kids against me, because

they're adults.

SB: Did you ever feel like "Gosh, I'm going to have

to join the Daughters of the American Revolution" or the PTA?

DN: I was already in the PTA! I was living in El Paso, Texas. I was a

Brownie Scout leader. Come on! I had street cred down there.

SB: This reporter who you called

into question at the Times, Mr. Eichenwald. He got your story

thrown out of Salon [with] a phone call to

the editor.

DN: It wasn't one phone call, believe me.

SB: Well, okay, continuous screaming phone calls and emails. Suddenly,

you're put into the limelight as...

DN: The flake?

SB: Well, you were not just described as a flake, but it was — "she's obsessed with

looking at pornography. And here this reporter (Eichenwald) is just trying to save

the children. Why doesn't she care about saving the children?" What do

you do when people get that picture of you as

cold and unfeeling and just ready to trample over all these poor

sex slaves with your calculated attempts to defend the first amendment.

I'm trying to conjure up some of the stuff you might have heard.

DN: You know, I don't mind criticism, when it's honest criticism

conducted in a normal, democratic forum — i.e., letters to the editor.

Things like that. I mean, somebody threatening to sue you is really

beyond the pale. But when people criticize me, there's always a

whole bunch of other people — there are never as many as the people who

criticize me, but the people who defend my point of view are often quite

eloquent. In the Salon piece, for example, there was a very active

discussion going on before that piece was pulled. There was dozens of

letters that came in, just in the first few hours. I was very

gratified by them. And my biggest regret about that piece being pulled,

and that there were legal threats made — was that the discussion got

shut down. And I'm really looking forward to starting that

discussion again.

I think it's a really important discussion. I think

child pornography needs to be de-mystified, and all the politics need to be broken down. And all of the First

Amendment issues need to be laid out on the table. And the

criticism — I don't know. I'm just getting too old to worry

about it.

SB: Are you a First Amendment absolutist? Or do you feel like there is

a certain place where you want to kick in a certain exception for those

under 18?

DN: I don't know. I mean, honestly? This is where people who I have

great respect for have taken issue with me, because in the Salon piece I said that there should be a vetting system put in place by the government so that legitimate researchers and journalists should be able to review what's on the web. There were critics who were very sympathetic to my opinion that child porn really needs to be looked at by civil society, who nevertheless said, "That's a terrible idea. To call for the government to put in place a system that decides that some people deserve to do that and other people don't. That's a lousy idea!" But I've also said before that I just don't know. I haven't come to a position about whether everyone should be able to look at child porn — that we should all just be able to look at records of assaults against children.

SB: Well there's a lot of scrutiny going on right now about who are the bodies of people who make decisions about what can be seen, or can't be seen — like the motion picture ratings association. It's always been shrouded in secrecy. Who are these people that decide that something's an "R," and something's an "X"? As it begins to get peeled away, and you look at the actual fallible human beings who are selected to these bodies, you say, "What the hell do they know? And this has nothing to do with democracy.

DN: Yeah. And, you know, really, when you look at the content of child porn, to the limited extent that people in civil society have been able to study child porn, a lot of it is older minors. A lot of it is a 14-year-old standing in a lake with her breasts exposed. Some juries and some judges will say that's not pornography, that's just simple nudity. Other judges and juries will say it's obscene and exploitative. So the definitions are very hard to parse out. But this is my irrational spot. I haven't got this all figured out yet. Because there is really awful stuff, too, of little kids, and there was no consent whatsoever. It's very horrible stuff. Some people talk about civil suits. There should be a way to bring civil suits against people who make this stuff and publicize it, because it's embarrassing, potentially. I just haven't figured it out yet.

See also:

The Perversions of Perverted Justice

Sex Expert Susie Bright Lets It All Out

Sex & Drugs & Susie Bright

World Sex Laws

My Opponent Pays For Gay Teen Bestiality

Their name is "Perverted Justice" — and something strange happens when you follow hyperlinks to their site from Wikipedia.

Their name is "Perverted Justice" — and something strange happens when you follow hyperlinks to their site from Wikipedia.

.jpg)