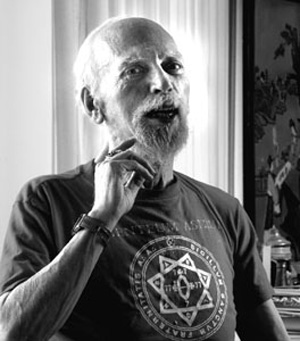

According to transhumanist Michael Anissimov

According to transhumanist Michael Anissimov, there's an even chance that we're looking at immortality or existential destruction in the next 20-40 years. Anissimov is only 23-years-old but he's already become an important figure in the transhumanist movement. While still in high school, he became founder and director of the Immortality Institute. He's been active with the World Transhumanist Association (WTA), and he is currently Fundraising Director, North America for the

Lifeboat Foundation.

Lifeboat Foundation describe themselves as "a nonprofit organization dedicated to encouraging scientific advancements while helping humanity survive existential risks and possible misuse of increasingly powerful technologies, including genetic engineering, nanotechnology, and robotics/AI as we move toward a

technological singularity."

Anissimov also blogs regularly at

Accelerating Future.

I interviewed him for my

NeoFiles Show. Jeff Diehl joined me.

To listen the full interview in MP3, click here.

RU SIRIUS: Let's start off talking

about immortality. And let's talk about it personally. Do you want to live forever?

MICHAEL ANISSIMOV: Oh, absolutely! For sure!

RU: Why?

MA: Because I have at least a thousand years of plans already. And in those thousand years, I'll probably make another thousand years of plans, and I don't see any end to that cycle.

RU: Do you see the quality of life improving for yourself and for most human beings?

MA: Yes, I do.

RU: Because I don't know if I want to live forever under Darwinian conditions. It gets tiring.

MA: I agree. It does. We need to take control of our own evolution before this would be a planet really worth living on. I don't think that thousands of years of war would be good for anyone. So things do need to improve.

RU: Yeah. Even having to pay… who can afford a thousand years?

MA: (Laughs) Well, you'll work for a thousand years...

RU: It's very expensive!

MA: Yeah, people are dying to retire. So it would help out if we had the robots doing a little bit more of the work.

JEFF DIEHL: So what's your itinerary for the next thousand years?

MA: I want to go spelunking in every major cave. I want to climb the highest peak on every continent. I want to write, like maybe at least ten nonfiction books and ten fiction books. Mmmm…

RU: Some people have done that in a lifetime.

MA: I know!

JD: Yeah, you're not very ambitious, man — come on!

MA: (Laughs) Think of ten possible lives you could live, and then think that you don't necessarily need to choose between them. You could live them back to back.

RU: On the other hand, you could pop your consciousness into several bodies and have them all living simultaneously for only a hundred years. Would that be the equivalent of living a thousand years?

MA: I don't think so. I think that would just be like having kids. Copying yourself would give rise to multiple independent strains of consciousness.

RU: Maybe there could be some kind of central person who could be taking in all of the experiences.

MA: There could be some information exchange, but...

RU: Aubrey de Grey, of course, is the hacker-biologist who has become very well known for saying that this is quite plausible in the near future. Is there any progress that he's pointed to, or that you can point to, since he really proclaimed the plausibility of immortality some time around the beginning of this century?

MA: Yeah. Recently Peter Thiel, former CEO of Paypal, offered three million dollars in matching funds for projects related to this. And they've started coming up with ways to actually use over a million dollars, I believe. They have the MitoSENS project and the LysoSENS projects.

RU: What are these projects about?

MA: Well, with LysoSENS — lysomal junk is this stuff that builds up between cells. And our natural metabolism doesn't currently have any way of breaking it down. So researchers are trying to exploit the law of microbial infallibility — the notion that no matter what organic material you're talking about, you're going to be able to find a microbe that can eat it. So they're searching for microbes that are capable of breaking down this junk. And they've been looking in places like... next to a Burger King, because people throw burgers on the ground and stuff like that. So there are special bacteria there that learn how to break down these organic compounds. And some of these researchers have even gotten permission to get soil samples from the people that run graveyards because that's where you'd expect to find the bugs. Basically, they're looking for specialized microbes that can dissolve that lysomal junk.

RU: IBM recently announced a naotechnology breakthrough. They said that "the breakthrough marks the first time chips have been made with a self-assembling nano-technology using the same process that forms seashells or snowflakes." This sounds like a really big deal.

MA: Yeah, it is! It's not the same thing though as molecular manufacturing, where you basically have a molecular assembly line that places each atom, one by one. It's not quite as intelligently controlled or productive, but it is a large breakthrough.

RU: Yeah, the word jumps out at me — "self-assembling." That sounds... you're not

too excited?

MA: (Skeptically) Ehhh. I mean, it's pretty exciting but people have been playing around with this stuff for a while

RU: OK. Let's move on to your current work — The Lifeboat Foundation This foundation is focused on existential risk, which is a board game, I think:

Camus v.

Sartre.

MA: (Laughs) Not exactly!

RU: I don't know how you win. It's probably like

Waiting for Godot: A Tragicomedy in Two Acts — the board game never arrives.

Anyway, in the discourse currently going around among people who are part of the transhumanist schemata and transhumanist world — there seems to be a turn from optimism towards a dialogue that's sort of apocalyptic. And the Lifeboat website seems to reflect that. Do you think that's true?

MA: I think it is true to a small extent. I think it's actually reflective of the maturing of the transhumanist movement. Because it's easy to say…

RU: "It's gonna be great!"

MA: Particularly when the dotcom boom was happening, everyone was, like, "Oh,

the future's gonna be great. No problems." You know... "We're making shitloads of cash. Everything's going to go well."

Now, we've had seven years of George Bush. We've been involved in two wars. We understand that reality isn't always peachy keen and we're going to have to deal with the consequences.

RU: So are people in the transhumanist world as worried as they sound, or is it partly political – trying to be responsible and ease concerns among people who are perhaps more paranoid than technophiles like yourself?

MA: No, it's very genuine. The more you understand about powerful technologies, the more you understand that they really do have the potential to hose us all, in a way that nuclear war can't.

RU: Give me your top two existential risks.

MA: Well, as

Dr. Alan Goldstein pointed out on your show a couple of weeks ago,

Synthetic Life is a huge risk because life is inherently designed to replicate in the wild. So life based on different chemical reactions could replicate much more rapidly than what we're accustomed to, like some sort of super-fungus. I think that's one of the primary risks. And the second risk would be artificial intelligence — human-surpassing artificial intelligence.

RU: So you're concerned about the

"robot wars" scenario — artificial intelligence that won't care that much for us? Do you have any particular scenarios that you're following?

MA: Well, I'd like to caution people to be careful what they see in the movies. Because this is one of those areas where people have been speculating about it for quite a few decades, and so much fictional material has been built around it...

RU: Actually, I believe everything in

.

MA: (Laughs) If you really look through those shows in a critical way, you see that they're full of blatant holes all over the place. Like, they can send a guy through time, but they can't send his clothes with him through time? (Laughs) In reality, I think that artificial intelligence is potentially most dangerous because it might not necessarily need to have a robotic body before it becomes a threat. An artificial intelligence that's made purely out of information could manipulate a wide variety of things on the internet. So it would have more power than we might guess.

RU: You've written a bit about the idea of Friendly AI. (We had Eliezer Yudkowsky on the show quite a while back, talking about this.) Do you see steps that can be taken to ensure that A.I. is friendly?

MA: Yeah! I'm totally in support of Eliezer and the Singularity Institute. I think that they're one of the few organizations that has a clue. And they're growing. I think that you've got to put a lot of mathematical eggheads working together on the problem. You can't just look at it from an intuitive point of view. You can actually understand intelligence on a mathematical level. It's a lot to ask. I think that friendly A.I. will be a tremendous challenge because there's just a lot of complexity in what constitutes a good person. And there's a lot of complexity in what constitutes what we consider common sense.

RU: Do you think the breakthrough might come through reverse engineering the human brain?

MA: It's possible but probably not.

RU: Good, because I don't think human beings are that friendly. I think the friendly A.I. has to be friendlier than human beings.

MA: It definitely does. And one way we could do that is by creating an A.I. that doesn't have a self-centered goal system. All creatures built by Darwinian evolution inherently have a self-centered goal system. I mean, before we became altruistic, we were extremely selfish. A reptile has eggs, and then the eggs hatch and he just walks off. He doesn't care about his kids. So this altruism thing is relatively recent in the history of evolution, and our psychology is still fundamentally self-centered.

JD: Isn't trying to plan for the nature of these future AI's kind of absurd because of the exponential superiority of their reasoning... if they even have what we would call reasoning? Can we really plan for this? It seems like once you hit a certain threshold, the Singularity, by definition is incomprehensible to us.

MA: I initially had the same issue. It seems impossible. But ask yourself, if you could choose, would you rather have an A.I. modeled after Hitler or would you rather have an A.I. modeled after Mother Teresa?

Regardless of how intelligent the A.I. becomes, it starts off from a distinct initial state. It starts off from a seed. So whatever it becomes will be the consequence of that seed making iterative changes on itself.

JD: But maybe in the first nano-second, it completely expunges anything that resembles human reasoning and logic because that's just a problem to them that doesn't need to be solved any more. And then beyond that — we have no fucking clue what they're going to move onto.

MA: It's true, but whatever it does will be based on the motivations it has.

JD: Maybe. But not if it re-wires itself completely…

MA: But if it rewired itself, then it would do so based on the motivations it originally had. I mean, I'm not saying it's going to stay the same, but I'm saying there is some informational similarity — there's some continuity. Even though it could be a low-level continuity, there's some continuity for an A.I. Also, you could ask the same question of yourself. What happens if a human being gains control over its own mind state.

RU: How we understand our motivations might be distinct from how we would understand our motivations if we had a more advanced intelligence.

MA: That's true.

RU: I'm going to move on to something that was on the Lifeboat web site that confounded me. It's labeled a News Flash. It says, "Robert A. Freitas Jr. has found preliminary evidence that diamond mechanosynthesis may not be reliable enough in ambient temperatures to sustain an existential risk from microscopic ecophagic replicators."

JD: (Joking) I had a feeling that was the case.

(Laughter)

RU: What the hell does that mean?!

MA: Robert's a bit of a wordy guy, but maybe I can explain it. You have an STM (Scanning Tunneling Microscope.) It's like a little needle that's able to scan a surface by measuring the quantum difference between the two surfaces. Diamond mechanosynthesis would just be the the ability to have a tiny needle-like robotic arm that places a single or perhaps two carbon atoms onto a pre-programmed place. So, in life, we are all based on proteins. Carbon isn't slotted in like in a covalent sense, which is the way that people that are working on nanotechnology are thinking of working. They're thinking of putting together pieces of carbon, atom by atom, to make a covalently bonding carbon. Robert's saying that it might be that the ambient temperature of the environment is too hot for that needle to work. So you'd need to have it in a vacuum or super-cooled environment for it to work.

RU: You did a good job of explaining that. Moving on, there's some talk on your site of the idea of relinquishment, which is deciding not to develop technologies. Is that even possible?

MA: Instead of relinquishment, I like to talk about selective development. You can't really relinquish technology too easily. But you can develop safeguards before technologies reach their maturity. And you can develop regulations that anticipate future consequences instead of always taking a knee-jerk reaction and saying: "Oh, this disaster happened; therefore we will now regulate."

RU: Of course, it's not really possible to regulate what everybody everywhere on the planet is doing.

MA: No, it's not.

RU: Are you familiar with Max More's Proactionary Principle?

MA: (Skeptically) Mmmm I'm...

RU: Too obvious?

MA: No, I don't fully agree with it. I do think that the Precautionary Principle has a point.

RU: Maybe I should say what it is. Basically, the Precautionary Principle says that with any technology we're developing, we should look ahead and see what the consequences are. And if the consequences look at all dire, then we should relinquish the technology. And Max More argues that we should also look at the possible consequences of

not developing the technology. For instance, if we don't develop nanotechnology, everybody dies.

MA: Well, I don't think that would happen.

RU: I mean, eventually… just as they have for millennia.

MA: Oh — everyone will

age to death!

RU: Right

MA: No, I agree that the balanced view looks at both sides of the equation. The Precautionary Principle's kind of been tarnished because there are people that are super-paranoid; and people who use it as an excuse to rule out things that they find ethically objectionable like therapeutic cloning.

RU: Well, you could take anything as an example. Look at automobiles. If we had looked ahead at automobiles — we could debate for hours whether they were a good idea. There would probably be less humans on the planet and there would probably be less distribution of medicine and food and all those things. On the other hand, we might not be facing global warming. It might be nice that there are less humans on the planet.

MA: Yeah, but in practice, if some invention is appealing and has large economic returns, then people are going to develop it no matter what.

RU: On the Lifeboat site, you have a list of existential risks. And people can sort of mark which existential risk they want to participate in or work on. I'd like to get your comments on a few of the risks that are listed. But before I go down a few of these things on the list, what do you think is up with the bees?

MA: The bees?

RU: The honeybees are dying off.

Einstein said we wouldn't survive if...

JD: … there's some contention about whether he actually said that. I heard that somebody tried to find that quote, and they weren't able to find it.

MA: What does this have to do with the bees?

RU: Einstein said that if all the honeybees died off, we'd all be dead in four years, or something like that.

JD: Yeah, because of the natural cycles that they support. Somebody else debunked that.

RU: Well, he was no Einstein. You better look into the bees because that could be an existential risk.

So here's one of the risks – or the risk aversion possibilities — listed on the site: Asteroid Shield.

MA: Well, someone once said that we're in a cosmic shooting gallery and it's only a matter of time before we get nailed. I wouldn't consider this to be a high priority, but in the interest of comprehensiveness, it would be a good idea if we had a way to deflect asteroids. Serious scientists have been looking at this issue and they decided that knocking it out with a nuclear bomb wasn't really going to work so well. It's too expensive and too unpredictable. So they're talking about attaching small rockets to slowly pull an asteroid off course.

JD: I recently read one idea — collect a lot of space junk and create one big object to alter the gravitational...

MA: Or you can put a little electro-magnetic rail gun on the surface and progressively fire off chunks of the asteroid, which will also alter its course. Even if you altered the trajectory of an incoming asteroid by a tiny amount, it would probably miss because earth is just kind of like a tiny dot in space. But right now, we don't have the capability. So if an asteroid were coming next year, we would be screwed.

RU: Right. And people have started talking about it. I mean, there has been sort of an advance in the level of paranoia about asteroids that come anywhere near us in recent years.

MA: One asteroid came about half of the way between us and the moon a while ago.

JD: Was it big enough to kill us?

MA: No. It was a hundred feet across, though — not bad.

RU: So how much chaos would that cause? I guess that would depend on where it landed.

MA: Measured in megatons, I think it would be about one Hiroshima.

JD: Oh, okay. We can handle that… as long as it doesn't land in San Francisco.

MA: (Laughs) Exactly! So I don't think the asteroids are an immediate concern. But it helps people comprehend the notion of extinction risks.

RU: The former NASA astronaut Rusty Schweickart has become involved in fighting off the asteroids. He used to be part of the

L5 Society. I think Ronald Reagan would say it's a way of uniting all the people of earth to fight against an enemy.

MA: Yeah!

RU: I think he talked about that in terms of aliens, not in terms of asteroids.

MA: Well, I think all existential risks, including the more plausible ones, do serve a function in uniting humanity, and I think that's a nice side effect.

RU: The particle accelerator shield — what's that about?

MA: Some people think — as we engage in increasingly high-powered particle accelerator experiments — something bad could happen. One standard idea is a strangelet, which is similar to an atom but much more compact. If a strangelet could absorb conventional matter into itself, and do so continuously, it could absorb the entire planet.

RU: Sort of like a black hole.

MA: Yes, very much like a black hole. It's another one of those situations where we want to instill a sense of caution in the minds of scientists. We don't want them to just dismiss these possibilities out of hand because it potentially threatens their funding. We want them to actually give it a little bit of thought.

RU: OK, what about "seed preserver."

MA: Oh, yeah! Well that's actually being done right now! The Norwegian government built a seed bank on some far north Arctic island. They're shoving some seeds in there, so I guess when the nanobots come, or the nuclear war comes and 99% of humanity is all gone, then we'll be able to go there, withdraw the seeds, and create life anew.

RU: You seem to be a believer in the Singularity. For me – maybe yes, maybe no. But I find it amusing that

Vernor Vinge could give a talk titled "What if the Singularity Does NOT Happen", the implication being that the idea that it might

not happen is a real stretch. Do you ever feel like you're in a cult — that people who believe in this share a peculiar reality?

MA: The word Singularity has become a briefcase word. People kind of want to put their pet ideas into it, so the actual idea has become kind of unclear in the minds of many people. To me, the Singularity is just the notion of an intelligence that's smarter than us. So if you say that you don't believe in the Singularity, it means that you believe that human beings are the smartest possible intelligence that this universe can hold.

RU: I guess what I don't believe is that it necessarily becomes a complete disjunction in history.

MA: But don't you think that homo sapiens are a quite complete disjunction from, say, homo erectus or chimps? We share 98% of the same DNA. So what if you actually used technology to surpass the human mind? I think you'd have something substantially more different from homo sapiens than homo sapiens was from their predecessors.

RU: Do you think it's more likely that we'll develop machines that are more intelligent than us and keep them exterior to us; or will we find some way of incorporating them into us? It seems to me, if you look at the passion that people have for being on the net, and being able to call up and get and link to all the information and all the intelligence on the planet, people are going to want this inside themselves. They're going to want to be able to have as much information and as much intelligence as everybody else. They'll want to unite with it.

MA: I think that would be a great thing, as long as people don't go using their intelligence for negative ends.

JD: Do you think this would happen gradually. Or do you think there would be this point in time where lots of people make choices like whether or not to merge? And then, maybe, the people who are afraid of that will want to stop people from doing it, and conflict...

MA: I think it could actually be somewhat abrupt, because once you have a superior intelligence, it can create better intelligence enhancement techniques for itself. So it could be somewhat abrupt. But I think that these smart entities could also find a way of keeping humanity on the same page and not making it like: "Oh, you have to choose… If your brother or your sister is not going into the great computer, then..."

RU: I think if it happens soon enough, it will be viewed as just another way of going online. You know, to young people, it will be just… "Yeah, this is how everybody's going online now."

MA: But if you had implants in your brain, it would be permanent.

RU: Do you think chaos is built into life? As the

Artificial Life people have been saying, life happens on the boundary between order and chaos. If chaos is an element of life, can machines include chaos?

MA: Well, uh — hmm. I think that people overestimate the power of chaos.

RU: As a

Patti Smith fan, I have to disagree.

MA: (Laughs) Well, it's such an appealing idea — chaos. But if you take a look at human blood and compare it to some random bit of muck you find in the ground, you'll see that it's highly regulated, and there are huge complements of homeostatic mechanisms in bodies that are constantly ordering things. Relative to the entropy in the air array outside; inside my body is a very orderly place, Life forms are very well organized pieces of matter.

RU: Right, but if you achieve complete homeostasis, then nothing happens.

MA: That's true. Life

does have to be on that boundary so it is challenging

RU: Here's a quote from an interview with you: "The idea of the Singularity is to transcend limitations by reengineering brains or creating new brains from scratch, brains that think faster with more precision, greater capabilities, better insights, ability to communicate and so on." OK. That sounds good, but what about pleasure, play, creativity, eroticism… and whatever it is you get from magic mushrooms? Where does all that go?

MA: (Laughs) I think all that's very important. I think about all those things.

RU: So you think that can be built that into the singularity?

MA: Yeah. Oh, for sure…

RU: David Pierce is the one person who really sort of deals with those ideas.

MA: Well, it's not really too PC to talk about it. But

when you take a psychedelic, you've changed your brain chemistry. With mushrooms, you flood your brain with this one psilocybin chemical. With technologies that let you actively change your own mind, it would be less of a shot in the dark. More precision modifications would be possible. And you could turn it on and off like a light switch, too. You could have much more control over it.

RU: Looking forward to it!

See Also:

Create an Alien, Win A-Prize

Why Chicks Don't Dig The Singularity

Death? No, Thank You

Prescription Ecstasy and Other Pipe Dreams

It's "The Breast Christmas Ever," promises California radio station KLLY. Whichever lucky listener wins their holiday-themed contest will receive a special prize — breast enlargement surgery.

It's "The Breast Christmas Ever," promises California radio station KLLY. Whichever lucky listener wins their holiday-themed contest will receive a special prize — breast enlargement surgery.

One woman, one very large and apparently out-of-control woman, has caused the resignation of a city councilman, the mayor, and the police chief of Snyder, Oklahoma. Libertarians across the blogosmear were quick to react with support for the First Amendment and condemnation of the religious sensibilities of the town and its churchgoing residents.

One woman, one very large and apparently out-of-control woman, has caused the resignation of a city councilman, the mayor, and the police chief of Snyder, Oklahoma. Libertarians across the blogosmear were quick to react with support for the First Amendment and condemnation of the religious sensibilities of the town and its churchgoing residents.

In 2000, while he was director of the Jefferson County Narcotics Enforcement Team, Tod Ozmun was investigated (but never charged) during an

In 2000, while he was director of the Jefferson County Narcotics Enforcement Team, Tod Ozmun was investigated (but never charged) during an