"Writing as a special talent

"Writing as a special talent became obsolete in the 19th century. The bottleneck was publishing."

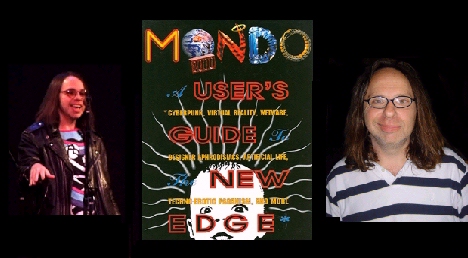

That bold statement came from Clay Shirky when I interviewed him for the NeoFiles webzine back in 2002. I never got around to asking him if that was an aesthetic judgment or a statement about economics and social relations.

But here's a contrasting viewpoint. Novelist William Burroughs met playwright Samuel Beckett, and after some small talk, Beckett looked directly at Burroughs and said, propitiously, "You're a writer." Burroughs instantly understood that Beckett was welcoming him into a very tiny and exclusive club — that there are only a few writers alive at any one time in human history. Beckett was saying that Burroughs was one of them. Everybody writes. Not everybody is a writer. Or at least, that's what some of us think...

Now the web — and its democratizing impact — has spread for over a decade. Over a billion people can deliver their text to a very broad public. It's a fantastic thing which gives a global voice to dissidents in various regions, makes people less lonely by connecting other people with similar interests and problems, ad infinitum.

But what does it mean for writers and writing? What does it mean for those who specialize in writing well?

I've asked ten professional writers, including Mr. Shirky, to assess the net's impact on writers. Here are their answers to the question...

Q: Is the internet good for writers and writing?

Mark Amerika

The short answer is yes, but as I suggest in my new book,

META/DATA, we probably need to expand the concept of writing to take into account new forms of online communication as well as emerging styles of digital rhetoric. This means that the educational approach to writing is also becoming more complex, because it's not just one (alphabetically oriented) literacy that informs successful written communication but a few others as well, most notably visual design literacy and computer/networking literacy.

As always, RU, you were ahead of the game — think how easy it is to text your name!

It helps to know how to write across all media platforms. Not only that, but to

become various role-playing personas whose writerly performance plays out in various multi-media languages across these same platforms. The most successful writer-personas now and into the future — at least those interested in "making a living" as you put it — will be those who can take on varying flux personas via the act of writing.

(And who isn't into making a living... What's the opposite? Conducting a death ritual for the consumer zombies lost in the greenwash imaginary?)

Think of this gem from Italo Calvino.

Writing always presupposes the selection of a psychological attitude, a rapport with the world, a tone of voice, a homogeneous set of linguistic tools, the data of experience and the phantoms of the imagination — in a word, a style. The author is an author insofar as he enters into a role the way an actor does and identifies himself with that projection of himself at the moment of writing.

The key is to keep writing, imaginatively. As Ron Sukenick once said: "Use your imagination or else someone else will use it for you." What better way to use it than via writing, and the internet is the space where writing is teleported to your distributed audience in waiting, no?

Mark Amerika has been the Publisher of Alt-X since it first went online in 1993. He is the producer of the Net-Art Trilogy, Grammatron. His books include META/DATA: A Digital Poetics and

In Memoriam to Postmodernism: Essays on the Avant-Pop (coedited with Lance Olsen). He teaches at the University of Colorado in Boulder.

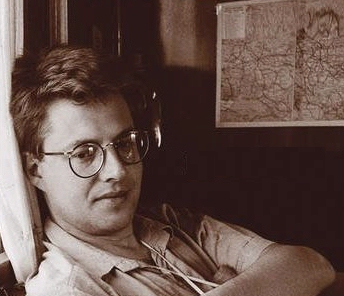

Erik Davis

In the face of this complex, hydra-headed query I'll simply offer the evidence and narrow perspective of one writer in a moderately grumpy mood: me.

I began my career as a freelance writer in 1989, and by the mid-90s was a modestly successful and up-and-coming character who wrote about a wide number of topics for a variety of print publications, both esoteric (

Gnosis, Fringeware Review) and slick (

Details, Spin). I got paid pretty good for a youngster—generally much better than I get paid now, when my career sometimes looks more and more like a hobby, but also less driven by external measures of what a “successful†writing career looks like.

I cannot blame my shrinking income entirely on the internet. My own career choices have been largely to write about what I want to write about, and my interests are not exactly mainstream. The early to mid-1990s was a very special time in American culture, a strange and giddy Renaissance where esoteric topics freely mixed and matched in a highly sampledelic culture. So I was able to write about outsider matters in a reasonably mainstream context.

My first book,

Techgnosis, which was about mystic and countercultural currents within media and technological culture, fetched a pretty nice advance. But once the internet bubble really started to swell, leading to the pop and then 9/11, that era passed into a more conservative, celebrity-driven, and niche-oriented culture, a development that relates to the rise of the internet but cannot be laid at its feet.

Many of the changes in the book industry and print publications are more obviously related to the rise of the internet. One of the worst developments for me has been the increasing brevity of print pieces, something I do blame largely on the fast-moving, novelty-driven blip culture of the internet and the blogosphere. When I started writing for music magazines, I wrote 2000-plus-word articles about (then) relatively obscure bands like Sonic Youth and Dinosaur Jr. Now I write 125-word reviews for Blender. I don't even try to play the game of penning celebrity-driven profiles in mainstream music mags anymore, where feature lengths have shrunk all around and the topics seem more driven by the publicists.

Shrinking space has definitely worked against my job satisfaction. I'm basically an essayist, though I often disguise myself as a critic or a journalist. Either way, it means that I am a long writer guy. I like to develop topics, approach them from different, often contradictory angles, and most of all, I like to polish the shit out of them so that the flow and the prose shine and bedazzle. On and offline, I find the internet-driven pressure to make pieces short, data-dense, and crisply opinionated — as opposed to thoughtful, multi-perspectival, and lyrical — rather oppressive, leading to a certain kind of superficial smugness as well as general submission to the forces of reference over reflection. I do enjoy writing 125-word record reviews though!

I also like to read and try to produce really good prose — prose that infuses nonfiction, whether criticism or journalism or essay, with an almost poetic and emotional sensibility that ideally reflects in style and form the content that one is expressing. But nonfiction discourse online is almost entirely driven by Content — which includes not only news and information, but also opinion, that dread and terrible habit that is kinda like canned thought. People have reactions, and yet feel a need to justify them, and so reach for a can of opinion, pop the lid, and spread it all over the bulletin board or the blog.

I'm really sick of opinions and of most of what passes for online debate. Even the more artful rhetorical elements of argument and debate are rarely seen amidst the food fights, the generic argumentative “moves,†the poor syntax, and the often lame attempts to bring a “fresh take†to a topic. This is not an encouraging environment from which to speak from the heart or the soul or whatever it is that makes living, breathing prose an actual source of sustenance and spiritual strength.

But it's all about adaptation, right? Though I'm still committed to books, I now write more online than off. I've been enjoying myself, although my definition of “making a living†has continued to sink ever farther from anything halfway reasonable. I've enjoyed writing for online pay publications like

Slate and

Salon, but the rates are depressing. As for my own writing at my Techgnosis.com, I'm still struggling to develop traffic in an environment that rewards precisely the kind of writing I don't really do. Some people really love the stuff I write there, but I take a lot of time on my posts and generally don't offer the sort of sharp opinions and super-fresh news and unseen links that tend to draw eyeballs.

At the same time, it's been enormously satisfying to find my own way into this vast and open form, and to elude the generic grooves of the blog form and really shape it into a medium for the kind of writing I want to do. (Don't get me wrong—some of my favorite writing and thinking anywhere appears online; BLDGBLOG is just the first that springs to mind.) It's been delicious to explore possibilities in nonfiction writing that all but the most obscure and arty print publications would reject, and to do so in a medium that is bursting with possible readers. I'm not into “private†writing; I write for and with readers in mind, and I think its great how the web allows linkages and alliances with like minds and crews (like 10 Zen Monkeys, or Reality Sandwich, or Boing Boing). And I know that readers who resonate with my stuff now stumble across it along myriad paths.

At the same time, I find it tough to keep at bay the online inclinations that in many ways I find corrosive to the type of writing I do — the desire to increase traffic, to post relentlessly, to write shorter and snappier, to obsessively check stats, to plug into the often tedious and ill-thought “debates†that will increase traffic but that too often fall far short of actually thinking about anything. I've met amazing like minds online, and participated in some stellar debates, but frankly that was years ago. Today things seem to be growing rather claustrophobic and increasingly cybernetic.

For example, I chose to not have a comments section on Techgnosis.com, because I didn't want to deal with spam. Plus I find most comments sections boring and/or tendentious and/or tough to read for one still invested in proper grammar. I figure that folks who wanted to respond can just send me emails, which they do, and which I have long made it a rule to answer. I'm pleased with my choice, though I also feel the absence of the sort of quick feedback loops of attention that satisfy the desire to make an impact on readers, and that, in an attention economy, have increasingly become the coin of the realm. But that coin—which is certainly not the same thing as actually being read—is a little thin.

Especially without some of the old coin in your pocket to back it up.

Erik Davis is author of The Visionary State: A Journey Through California's Spiritual Landscape and Techgnosis: Myth, Magic & Mysticism in the Age of Information.

He writes for Wired, Bookforum, Village Voice and many other publications. He posts frequently at his website at techgnosis.com

Mark Dery

Who, exactly, is making a living shoveling prose online? Glenn "Instapundit" Reynolds? Jason Kottke? Josh Marshall? To the best of my knowledge, only a vanishingly tiny number of bloggers are able to eke out an existence through their blogging, much less turn a healthy profit.

For now, visions of getting rich through self-publishing look a lot like envelope-stuffing for the cognitive elite — or at least for insomniacs with enough time and bandwidth to run their legs to stumps in their electronic hamster wheels, posting and answering comments 24/7. As a venerable hack toiling in the fields of academe, I

love the idea of being King of All Media without even wearing pants, which is why I hope that some new-media wonk like Jason Calacanis or Jeff Jarvis finds the Holy Grail of self-winding journalism — i.e., figuring out how to make online writing self-supporting.

Meanwhile, the sour smell of fear is in the air. Reporting — especially investigative reporting, the lifeblood of a truly adversarial press — is labor-intensive, money-sucking stuff, yet even

The New York Times can't figure out how to charge for its content in the Age of Rip, Burn, and Remix. To be sure, newspapers are hemorrhaging readers to the Web, and fewer and fewer Americans care about current events and the world outside their own skulls. But the other part of the problem is that Generation Download thinks information wants to be free, everywhere and always, even if some ink-stained wretch wept tears of blood to create it.

Lawrence Lessig talks a good game, but I still don't understand how people who live and die by their intellectual property survive the obsolescence of copyright and the transition to the gift economy of our dreams. I mean, even John Perry Barlow, bearded evangelist of the coming netopia, seems to have taken shelter in the academy. Yes, we live in the golden age of achingly hip little 'zines like

Cabinet and

The Believer and

Meatpaper, and I rejoice in that fact, but most of them pay hen corn, if they pay at all.

As someone who once survived (albeit barely) as a freelancer, I can say with some authority that the freelance writer is going the way of the Quagga. Well, at least

one species of freelance writer: the public intellectual who writes for a well-educated, culturally literate reader whose historical memory doesn't begin with

Dawson's Landing. A professor friend of mine, well-known for his/her incisive cultural criticism, just landed a column for PopMatters.com. Now, a column is yeoman's work and it doesn't pay squat. But s/he was happy to get the gig because she wanted to burnish her brand, presumably, and besides, as she noted, "Who does, these days?" (Pay, that is.)

The Village Voice's Voice Literary Supplement used to offer the Smartest Kids in the World a forum for long, shaggy screeds; now, newspapers across the country are shuttering their book review sections and the Voice is about the length (and depth) of your average Jack Chick tract and shedding pages by the minute.

So those are the grim, pecuniary effects of the net on writers and writing. As for its literary fallout, print editors are being stampeded, goggle-eyed, toward a form of writing that presumes what used to be called, cornily enough, a "screenage" paradigm: short bursts of prose — the shorter the better, to accommodate as much eye candy as possible. Rupert Murdoch just took over

The Wall Street Journal, and is already remaking that august journal for blip culture: article lengths are shrinking. Shrewdly, magazines like

The New Yorker understand that print fetishists want their print

printy — McLuhan would have said Gutenbergian — so they're erring on the side of length, and Dave Eggers and the

Cabinet people are emphasizing what print does best: exquisite paper stocks, images so luxuriously reproduced you could lower yourself into them, like a hot bath.

Also, information overload and time famine encourage a sort of flat, depthless style, indebted to online blurblets, that's spreading like kudzu across the landscape of American prose. (The English, by contrast, preserve a smarter, more literary voice online, rich in character; not for nothing are Andrew Sullivan and Christopher Hitchens two of the web's best stylists.) I can't read people like Malcolm Gladwell, whose bajillion-selling success is no surprise when you consider that he aspires to a sort of in-flight magazine weightlessness, just the sort of thing for anxious middle managers who want it all explained for them in the space of a New York-to-Chicago flight. The English language dies screaming on the pages of Gladwell's books, and between the covers of every other bestseller whose subtitle begins, "How..."

Another fit of spleen: This ghastly notion, popularized by Masters of Their Own Domain like Jeff Jarvis, that every piece of writing is a "conversation." It's a no-brainer that writing is a communicative act, and always has been. And I'll eagerly grant the point that

composing in a dialogic medium like the net is like typing onstage, in Madison Square Garden, with Metallica laying down a speed metal beat behind you. You're writing on the fly, which is halfway between prose and speech. But the Jarvises of the world forget that not all writing published online is written online. I dearly loathe Jarvis's implication that all writing, online or off, should sound like water-cooler conversation; that content is all that matters; that foppish literati should stop sylphing around and submit to the tyranny of the pyramid lead; and that any mind that can't squeeze its thoughts into bullet points should just die. This is the beige, soul-crushing logic of the PowerPoint mind. What will happen, I wonder, when we have to write for the postage-stamp screen of the iPhone? The age of IM prose is waiting in the wings...

Parting thoughts: The net has also open-sourced the cultural criticism business, a signal development that on one hand destratifies cultural hierarchies and makes space for astonishing voices like the people behind bOING bOING and BLDGBLOG and Ballardian. Skimming reader comments on Amazon, I never cease to be amazed by the arcane expertise lurking in the crowd; somebody, somewhere, knows everything about something, no matter how mind-twistingly obscure. But this sea change — and it's an extraordinary one — is counterbalanced by the unhappy fact that off-the-shelf blogware and the comment thread make everyone a critic or, more accurately, make everyone

think they're a critic, to a minus effect. We're drowning in yak, and it's getting harder and harder to hear the insightful voices through all the media cacophony. Oscar Wilde would be just another forlorn blogger out on the media asteroid belt in our day, constantly checking his SiteMeter's Average Hits Per Day and Average Visit Length.

Also, the Digital Age puts the middlebrow masses on the bleeding edge. Again, a good thing, and a symmetry break with postwar history, when the bobos were the "antennae of the race," as Pound put it, light years ahead of the leadfooted bourgeoisie when it came to emergent trends. Now even obscure subcultures and microtrends tucked into the nooks and crannies of our culture are just a Google search away. Back in the day, a subcultural spelunker could make a living writing about the cultural fringes because it took a kind of pop ethnographer or anthropologist to sleuth them out and make sense of them; it still takes critical wisdom to make sense of them, but sleuthing them out takes only a few clicks.

Do I sound bitter? Not at all. But we live in times of chaos and complexity, and the future of writing and reading is deeply uncertain. Reading and writing are solitary activities. The web enables us to write in public and, maybe one day, strike off the shackles of cubicle hell and get rich living by our wits. Sometimes I think we're just about to turn that cultural corner. Then I step onto the New York subway, where most of the car is talking nonstop on cellphones. Time was when people would have occupied their idle hours between the covers of a book. No more. We've turned the psyche inside out, exteriorizing our egos, extruding our selves into public space and filling our inner vacuums with white noise.

Mark Dery is the author of The Pyrotechnic Insanitarium: American Culture on the Brink and Escape Velocity: Cyberculture at the End of the Century. His 1993 essay "Culture Jamming: Hacking, Slashing, and Sniping in the Empire of the Signs" popularized the term "culture jamming" and helped launch the movement.

He teaches media criticism and literary journalism in the Department of Journalism at NYU and blogs at markdery.com

Jay Kinney

It's a mixed blessing.

If the hardest part of writing is just making yourself sit there and write, and what used to be a typewriter and a blank sheet of paper has been transformed into a magical portal to a zillion fascinating destinations, then the internet can be a giant and addictive distraction.

On the other hand, it's a quick and simple way to do research without ever leaving your chair, and that can be a real time-saver.

So, on those counts at least — color me ambivalent.

Jay Kinney is the author of Hidden Wisdom: A Guide to the Western Inner Traditions (with Richard Smoley), and The Inner West: An Introduction to the Hidden Wisdom of the West. He was the editor of CoEvolution Quarterly and Gnosis magazine.

Paul Krassner

For me as a writer, the internet has become indispensable; if only in terms of researching it saves so much time and energy. Google et al are miraculous.

Word processing has changed the nature of editing, and without the dread of typing a whole page again; I can change things as I go along, surrendering to delusions of perfection.

I have become as much in awe of Technology as I am of Nature. And although I blog for free, occasional paid assignments have fallen into my lap as a result.

Better than lapdancing.

Paul Krassner was Publisher/Editor of the legendary satire magazine, The Realist.

He started the classic satirical publication The Realist, founded the Yippies with Abbie Hoffman and Jerry Rubin and has written billions and billions of books including his most recent: One Hand Jerking: Reports from an Investigative Satirist. Krassner posts regularly at paulkrassner.com

Adam Parfrey

The internet has made research much easier, which is both good and bad. It's good not to be forced to go libraries to fact check and throw together bibliographic references. But it's bad not to be forced to do this, since it diminishes the possibility of accidental discovery. Physically browsing on library stacks and at used bookstores can lead to extraordinary discoveries. One can also discover extraordinary things online, too, but the physical process of doing so is somehow more personally gratifying.

The internet has both broadened and limited audiences for books at the same time. People outside urban centers can now find offbeat books that personally intrigue them. But the interest in physical books overall seems diminished by the satiation of curiosity by a simple search on the internet, and the distraction of limitless data smog.

The internet has influenced my decision as a publisher to move away from text-only books to ones with a more multimedia quality, with photos, illustrations and sometimes CDs or DVDs.

I like the internet and computers for their ability to make writers of nearly everyone. I don't like the internet and computers for their ability to make sloppy and thoughtless writers of nearly everyone.

Overall, it's an exciting world. I'm glad to be alive at this time.

Adam Parfrey is Publisher with Feral House and Process Media, and author of the classic Apocalypse Culture, among many other books.

Douglas Rushkoff

I'd say that it's great for writing as a cultural behavior, but maybe not for people who made their livings creating text. There's a whole lot more text out there, and only so much time to read all this stuff. People spend a lot of their time reading text on screens, and don't necessarily want to come home and read text on a page after that. Reading a hundred emails is really enough daily reading for anyone.

The book industry isn't what it used to be, but I don't blame that on the internet. It's really the fault of media conglomeration. Authors are no longer respected in the same way, books are treated more like magazines with firm expiration dates, and writers who simply write really well don't get deals as quickly as disgraced celebrities or get-rich-quick gurus.

This makes it harder for writers to make a living writing. To write professionally means being able to craft sentences and paragraphs and articles and books that communicate as literature. Those who care about such things should rise to the top.

But I think many writers — even good ones — will have to accept the fact that books can be loss-leaders or break-even propositions in a highly mediated world where showing up in person generates the most income.

Douglas Rushkoff is a noted media critic who has written and hosted two award-winning Frontline documentaries that looked at the influence of corporations on youth culture — The Merchants of Cool and The Persuaders.

Recent books include Get Back in the Box: How Being Great at What You Do Is Great for Business and Nothing Sacred: The Truth About Judaism. He is currently writing a monthly comic book, Testament for Vertigo. He blogs frequently at Rushkoff.com/blog.php

Clay Shirky

Dear Mr. Sirius,

I read with some interest your request to comment on whether Herr Gutenberg's new movable type is good for books and for scribes. I have spent quite a bit of time thinking about the newly capable printing press, and though the invention is just 40 years old, I think we can already see some of the outlines of the coming changes.

First, your question "is it good for books and for scribes?" seems to assume that what is good for one must be good for the other. Granted, this has been true for the last several centuries, but the printing press has a curious property — it reduces the very scarcity of writing that made scribal effort worthwhile, so I would answer that it is great for books and terrible for scribes. Thanks to the printing press, we are going to see more writing, and more kinds of writing, which is wonderful for the reading public, and even creates new incentives for literacy. Because of these improvements, however, the people who made their living from the previous scarcity of books will be sorely discomfited.

In the same way that water is more vital than diamonds but diamonds are more expensive than water, the new abundance caused by the printing press will destroy many of the old professions tied to writing, even as it puts in place new opportunities as yet only dimly with us. Aldus Manutius, in Venice, seems to be creating a market for new kinds of writing that the scribes never dreamt of, and which were impossible given the high cost of paying someone to copy a book by hand.

There is one thing the printing press does not change, of course, which is the scarcity of publishing. Taking a fantastical turn, one could imagine a world in which everyone had not only the ability to read and write but to publish as well. In such a world, of course, we would see the same sort of transformation we are seeing now with the printing press, which is to say an explosion in novel forms of writing. Such a change would also create enormous economic hardship for anyone whose living was tied to earlier scarcities. Such a world, as remarkable as it might be, must remain merely imaginative, as the cost of publishing will always be out of reach of even literate citizens.

Yours,

Clay Shirky, Esq.

Clay Shirky consults on the rise of decentralized technologies for Nokia, the Library of Congress, and the BBC. He's an adjunct professor in NYU's graduate Interactive Telecommunications Program (ITP), where he teaches a course in "Social Weather," examining ways of understanding group dynamics in online spaces.

His writing has appeared in Business 2.0, New York Times, the Wall Street Journal, and Wired, among other publications.

John Shirley

The internet has some advantages for writers, which I gladly exploit; it offers some access to new audiences, it offers new venues... But it has even more disadvantages.

A recent study suggested that young people read approximately half as much as young people did before the advent of the internet and videogames. While there are enormous bookstores, teeming with books, chain stores and online book dealing now dominate the book trade and it may be that there are fewer booksellers overall. A lot of fine books are published but, on the whole, publishers push for the predictable profit far more than they used to, which means they prefer predictable books. Editors are no longer permitted to make decisions on their own. They must consult marketing departments before buying a book. Book production has become ever more like television production: subordinate to trendiness, and the anxiety of executives.

And in my opinion this is partly because a generation intellectually concussed by the impact of the internet and other hyperactive, attention-deficit media, is assumed, probably rightly, to want superficial reading.

I know people earnestly involved in producing dramas for iPod download and transmission to iPhones. Obviously, productions of that sort are oriented to small images in easy-to-absorb bites. Episodes are often only a few minutes long. Or even shorter. Broadband drama, produced to be seen on the internet, is also attention-deficit-oriented. I've written for episodic television and have known the frustration of writers told to cut their "one hour" episodes down to 42 minutes, so that more commercials can be crammed in. Losing ten minutes of drama takes a toll on the writing of a one hour show — just imagine the toll taken by being restricted to three-minute episodes. Story development becomes staccato, pointlessly violent (because that translates well to the form), childishly melodramatic, simple minded to the extreme.

All this may be an extension of the basic communication format forged by the internet: email, chatrooms, instant messages, board postings, blogs. Email is usually telegraphic in form, compact, and without the literary feel that letters once had; communication in chatrooms is reduced to soundbites that will fit into the little message window and people are impatient in chatrooms, unwilling to wait as a long sentence is formulated; instant messages are even more compressed, superficial, and not even in real English; board postings may be lengthier but if they are, no one reads them.

Same goes for blogs. They'd better be short thoughts or — for the most part — few will trouble to read them. The internet is always tugging at you to move on, surf on, check this and that, talk to three people at once. How do you maintain long thoughts, how do you stretch out intellectually, in those conditions? Sometimes at places like The Well, perhaps, people are more thoughtful. But in general, online readers are prone to be attention challenged.

Reading at one's computer is, also, not as comfortable as reading a book in an armchair — so besides the distractions, it's simply a drag to spend a lot of time reading a single document online. But people spend a great deal of time and energy online, time and energy which is then not available for that armchair book. Occasionally someone breaks the rules and puts long stories online, as

Rudy Rucker has done, admirably well, posting new stories by various writers at flurb.net. But for the most part, the internet is inimical to stretching out, literarily.

The genie is out of the bottle, and we cannot go back. But it would be well if people did not misrepresent the literary value of writing for the internet.

John Shirley was the original cyberpunk SF writer, but he also writes in other genres including horror. He wrote the original script for The Crow and has written for television including Deep Space Nine, Max Headroom, and Poltergeist: The Legacy.

His books include the Eclipse Trilogy, Wetbones, The Other End and his latest — a short story collection Living Shadows: Stories: New & Preowned. He writes lyrics for Blue Oyster Cult. Shirley's own online indulgence is his site Signs of Witness.

Michael Simmons

Concerning the internet, yes, many thoughts. None of them good.

The advent of personal computers has been ruinous. Empowering, my ass. Suddenly everyone's a writer. As someone who's been a professional writer my entire life, I now sit for hours every day and answer e-mails. I don't mind if the subject has substance, like this, but the onslaught of e-media, e-spam, e-requests for money, stupid e-jokes, e-advertisements, etc., is painful. I'm chained to a machine. Editors say they simply can't respond to all the e-mails they receive. Telephonic communication was quicker and easier.

Used to be I sat at an alphabet keyboard (called typewriters in my day) when I had an assignment or inspiration. Now it's all I do. Go to a library? Why? You can get what you need on the internet. Which means I've been suffering from Acute Cabin Fever since 1999 (when I tragically signed up for internet access). Sure, I

could get off my ass and go to a library, but the internet is like heroin. Why take a walk in the park when you can boot up and find beauty behind your eyelids or truth from the MacBook? (Interesting that the term 'boot-up' is junkie-speak.)

I only got a word processor in 1990. I used a typewriter until then. My writing was no different before I could instantly re-write. I had to think about what I was going to write before applying fingertip to key. Now I'm terribly careless. I make mistakes that I never made pre-processing. Certainly literature hasn't improved (nor has art, music, film or anything else). Instead of reading Charles Olson or Rimbaud or Melville or Voltaire or Terry Southern, now people spend all day playing with their computers and endless varieties of applications.

I hear my friends — all smart — kvelling about some new piece of software. You'd think they'd cured cancer. We're a planet of marks getting our bank accounts skimmed by Bill Gates and Steven Jobs. Gates and Jobs (and

yer pal Woz) ought to be disemboweled — yes,

on the internet — and their carcasses left to rot on www.disemboweledcyberthieves.com.

Furthermore, I get nauseous thinking of the days, weeks, months I've spent on the phone with tech support. All these robber baron geeks are loaded, yet they can't even perfect the goddamn things.

The world of LOL and iirc and this hideous perpetual junior high language has not encouraged quality-lit. Have you looked at my former employer the

L.A. Weekly lately? It's created by illiterates promoting bad and overpriced music, art, film, etc. There's a glut of so-called writers and if they're 22 and have big tits, many editors will give them work before I get any. It's no coincidence that my payments and assignments for freelancing have diminished in the last 8 years.

I was a happy nappy-takin' pappy 'fore the advent of these glorified television sets. Now my eyes hurt at the end of every day from the glow of the monitor. RU, I'm not happy that you — a brilliant man who has kept Yippie spirit alive — promote these contraptions. I didn't even have a phone answering machine until 1988 when I was 33. Everything was better before this glut of machinery entered my life. It's quadrupled my monthly bills and swamps me with useless information.

No, it hasn't fired my imagination but, yes, I can't get no satisfaction.

Michael Simmons edited the National Lampoon in the ‘80s. He has written for LA Weekly, LA Times, Rolling Stone, High Times, and The Progressive. Currently, he blogs for Huffington Post and he and Tyler Hubby are shooting a documentary on the Yippies

Edward Champion

The Internet is good for writers for several reasons: What was once a rather clunky process of querying by fax, phone, and snail-mail has been replaced by the mad, near-instantaneous medium of e-mail, where the indolent are more easily sequestered from the industrious. The process is, as it always was, one of long hours, haphazard diets, and rather bizarre forms of self-promotion. But clips are easily linkable. Work can be more readily distributed. And if a writer maintains a blog, there is now a more regular indicator of a writer's thought process.

The stakes have risen. Everyone who wishes to survive in this game must operate at some peak and preternatural efficiency. Since the internet is a ragtag, lightning-fast glockenspiel where thoughts, both divine and clumsy, are banged out swifter with mad mallets more than any medium that has preceded it, an editor can get a very good sense of what a writer is good for and how he makes mistakes. While it is true that this great speed has come at the expense of long-form pieces and even months-long reporting, I believe the very limitations of this current system are capable of creating ambition rather than stifling it.

If the internet was committing some kind of cultural genocide for any piece of writing that was over twenty pages, why then has the number of books published increased over the past fifteen years? Some of the old-school types, like John Updike, have decried the ancillary and annotated aspects of the Internet, insisting that there is nothing more to talk about than the book. But if a book is a unit transmitting information from one person to another, then why ignore those on the receiving end? For are they not part of this process? Writing has been talked about ever since Johann Gutenberg's great innovation caused many classical works to be disseminated into the public consciousness, and thus spawned the Renaissance.

What we are now experiencing may have an altogether different scale, but it is not different in effect. The profusion of written thoughts and emotions is certainly overwhelming, but the true writer is likely to be a skillful and highly selective reader, and thus has many jewels to select from, to be inspired by, to be wowed by, and to otherwise cause the truly ambitious to carry forth with passion and a whip-smart disposition.

Edward Champion's work has appeared in The LA Times, Chicago Sun-Times, and Newsday, as well as more disreputable publications.

His Bat Segundo podcast — which you can find at his website at edrants.com — has featured interviews with the likes of T.C. Boyle, Brett Easton Elllis, Octavio Butler, John Updike, Richard Dawkins, Amy Sedaris, David Lynch, Martin Amis, and William Gibson.

Contributor Books

Mark Amerika

Erik Davis

Mark Dery

Jay Kinney

Paul Krassner

Adam Parfrey

Douglas Rushkoff

John Shirley

See Also:

How The Internet Disorganizes Everything

When Cory Doctorow Ruled The World

David Sedaris Exaggerates For Us All

How The iPod Changes Culture

Thou Shalt Realize the Bible Kicketh Ass

If you're looking for a unique solution, you can only win when you...stop looking and finally give up.

If you're looking for a unique solution, you can only win when you...stop looking and finally give up.

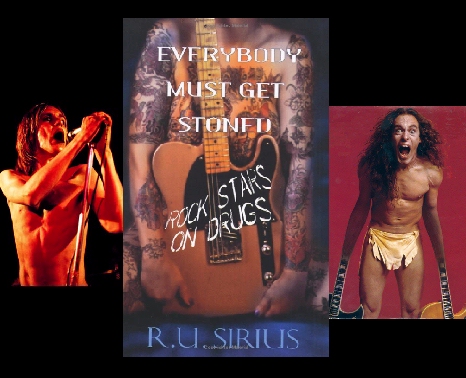

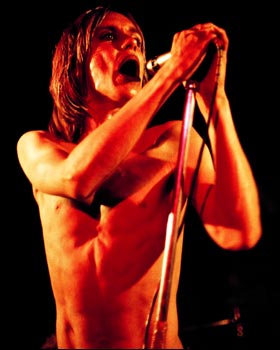

In 1969-1970, Iggy Pop and his seminal proto-punk band the Stooges lived together outside Detroit in a house they nicknamed "Fun House." (They also

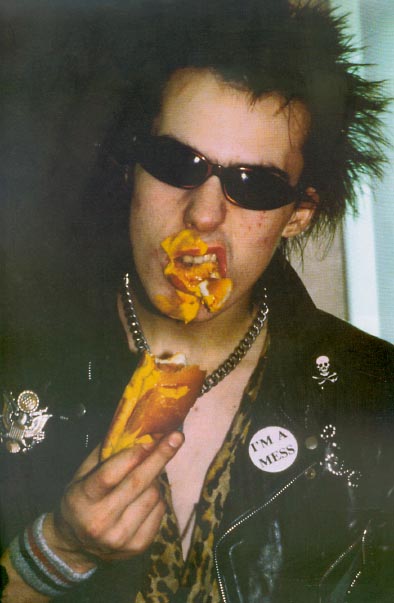

In 1969-1970, Iggy Pop and his seminal proto-punk band the Stooges lived together outside Detroit in a house they nicknamed "Fun House." (They also  Dee Dee Ramone found himself at a party in London, hanging out for a few moments in the bathroom snorting great quantities of speed. It wasn't the sort of place you'd want to hang out for too long, as Dee Dee quickly noticed that the bathroom was disgusting — sinks, toilets, everything was full of vomit, piss, and shit. Sid Vicious — a key figure in the London punk scene but not yet a member of the Sex Pistols — wandered in and asked Dee Dee if he had anything to get high on, so Dee Dee generously gave Sid some of his crank. Vicious pulled out a syringe, stuck it into a toilet filled with puke and piss, and then loaded it with speed and shot himself up.

Dee Dee Ramone found himself at a party in London, hanging out for a few moments in the bathroom snorting great quantities of speed. It wasn't the sort of place you'd want to hang out for too long, as Dee Dee quickly noticed that the bathroom was disgusting — sinks, toilets, everything was full of vomit, piss, and shit. Sid Vicious — a key figure in the London punk scene but not yet a member of the Sex Pistols — wandered in and asked Dee Dee if he had anything to get high on, so Dee Dee generously gave Sid some of his crank. Vicious pulled out a syringe, stuck it into a toilet filled with puke and piss, and then loaded it with speed and shot himself up.

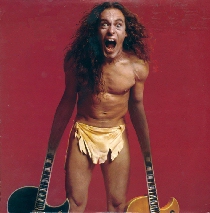

The right-wing rocker Ted Nugent is known for being very antidrug and very prowar. The Motor City Madman happily calls out any pussy-ass traitor not ready to grab a gun or a bomb or a nuke and show those towelheads that we mean business. But back during the glory years of the Vietnam war, this most macho chickenhawk in the Republican firmament went to extremes to make sure his own pussy ass didn't end up in Vietnam, and he used drugs to do it.

The right-wing rocker Ted Nugent is known for being very antidrug and very prowar. The Motor City Madman happily calls out any pussy-ass traitor not ready to grab a gun or a bomb or a nuke and show those towelheads that we mean business. But back during the glory years of the Vietnam war, this most macho chickenhawk in the Republican firmament went to extremes to make sure his own pussy ass didn't end up in Vietnam, and he used drugs to do it.

Japan has a reputation for searching rock stars for drugs. Most famously, Paul McCartney spent some time in jail after going through Japanese customers (see also the chapters: "The Beatles on Drugs" and "Big Busts and Big Deals"). So when Guns n' Roses guitarist Izzy Stradlin was warned by his manager to get rid of any drugs he might have before going through customers in Japan, Stradlin put them someplace he knew he wouldn't lose them — in his stomach. He must have had quite a stash, because he wound up in a coma for 96 hours.

Japan has a reputation for searching rock stars for drugs. Most famously, Paul McCartney spent some time in jail after going through Japanese customers (see also the chapters: "The Beatles on Drugs" and "Big Busts and Big Deals"). So when Guns n' Roses guitarist Izzy Stradlin was warned by his manager to get rid of any drugs he might have before going through customers in Japan, Stradlin put them someplace he knew he wouldn't lose them — in his stomach. He must have had quite a stash, because he wound up in a coma for 96 hours.

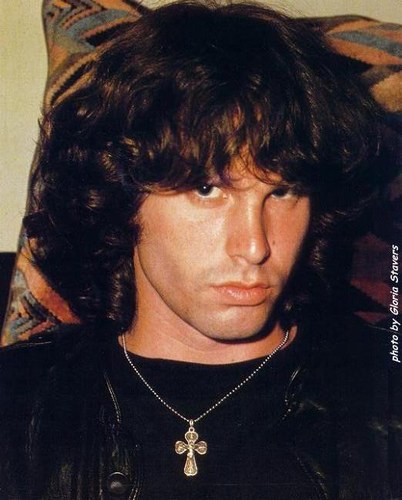

In

In  In his mid-1970s heyday, Los Angeles declared "Elton John Week." To celebrate, the glam rock pasha invited his relatives out to L.A. to celebrate. Allegedly, Elton took 60 Valiums, jumped into a hotel pool, and shouted, "I'm going to die." His grandmother was heard to comment: "I suppose we're going to have to go home now."

In his mid-1970s heyday, Los Angeles declared "Elton John Week." To celebrate, the glam rock pasha invited his relatives out to L.A. to celebrate. Allegedly, Elton took 60 Valiums, jumped into a hotel pool, and shouted, "I'm going to die." His grandmother was heard to comment: "I suppose we're going to have to go home now."

In a 1999 High Times interview, Ozzy talked about the time he had the best coke he'd ever had. He said, "I'm lying by the pool one day and I met this guy and I ask him, 'You want to do some coke?' He goes, 'no no no.' I'm whacking this stuff up my nose, it's a brilliant sunny day, and this guy's sitting there with one of those reflectors under his chin getting a suntan. I say, 'What do you do.' He says, 'I work for the government.' 'Uh... what do you do with the government?' 'I work for the drug squad.' I sez, 'You're fucking joking.' He shows me his badge. I fuckin' flipped...flames were coming out of my fingers, man. He says, 'Oh you're all right. I'm the guy that got you the coke.'"

In a 1999 High Times interview, Ozzy talked about the time he had the best coke he'd ever had. He said, "I'm lying by the pool one day and I met this guy and I ask him, 'You want to do some coke?' He goes, 'no no no.' I'm whacking this stuff up my nose, it's a brilliant sunny day, and this guy's sitting there with one of those reflectors under his chin getting a suntan. I say, 'What do you do.' He says, 'I work for the government.' 'Uh... what do you do with the government?' 'I work for the drug squad.' I sez, 'You're fucking joking.' He shows me his badge. I fuckin' flipped...flames were coming out of my fingers, man. He says, 'Oh you're all right. I'm the guy that got you the coke.'"

That "naked"

That "naked"  Facebook users have already started

Facebook users have already started

Wednesday South Park

Wednesday South Park  A Utah newspaper

A Utah newspaper

.jpg) In the end, an ungrateful Joe the Plumber

In the end, an ungrateful Joe the Plumber  "Dear Sarah Palin," read a

"Dear Sarah Palin," read a  45 minutes after Obama was elected, Roger Ebert

45 minutes after Obama was elected, Roger Ebert

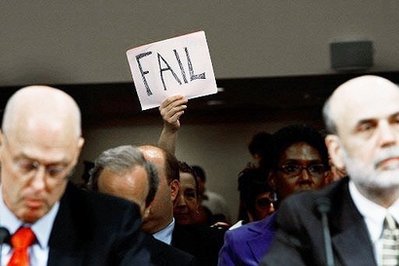

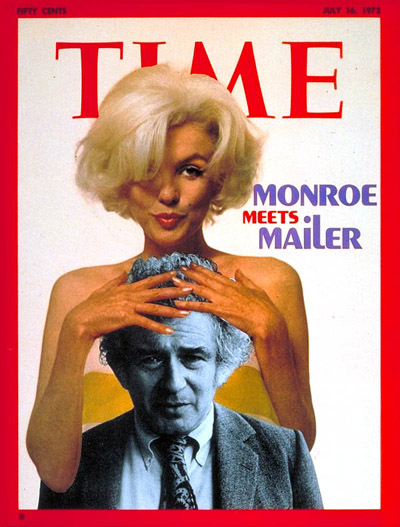

After "new left" protesters clashed with police during the 1968 Democratic convention,

Norman Mailer had predicted that a torn country "will be fighting for forty years."

(One critic

After "new left" protesters clashed with police during the 1968 Democratic convention,

Norman Mailer had predicted that a torn country "will be fighting for forty years."

(One critic  The violent clashes at the '68 convention haunted Democrats — but one liberal who never understood the

protesters was Barack Obama's own mother.

The violent clashes at the '68 convention haunted Democrats — but one liberal who never understood the

protesters was Barack Obama's own mother.

The morning after Obama was elected, he was

told he'd been expected by Alice Walker, author of

The morning after Obama was elected, he was

told he'd been expected by Alice Walker, author of

.jpg)

.jpg)

McFarlane's book even detours to report that the females in the book were feeling left out.

McFarlane's book even detours to report that the females in the book were feeling left out.